International Sloth Day

Thursday, October 20th, 2022

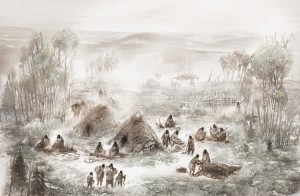

The sloth is an animal that uses its claws to hang from branches.

Credit: © Michael Fogden, Bruce Coleman, Inc.

Slow down and wait a minute! Today is International Sloth Day, a day to slow our speed and appreciate the world’s slowest mammal. While many species evolve to eat more, sloths have done the opposite! They evolved in a way that allows them to eat less and survive just by slowing down.

A sloth is a mammal that has a slow and peculiar way of moving. Sloths spend nearly all of their time in rain forest trees in Central and South America, where they travel upside down, hanging from branches with their hooklike claws. Hanging upside down requires almost no energy for a sloth. They can fall asleep in this position and may even stay suspended in the trees for some time after they die. There are two main groups of sloths. One is two-toed and the other is three-toed.

All sloths have small heads, and their noses are blunt. They have peglike teeth. Two-toed sloths also have large sharp teeth at the front of the mouth. Both measure 15 to 30 inches (38 to 76 centimeters) long and weigh 5 to 23 pounds (2.3 to 10.5 kilograms). Their long, coarse fur grows in the opposite direction as that of other mammals, from the stomach towards the back. This allows rain water to easily drain off the body as the sloth hangs. The fur ranges from grayish to brownish in color, which makes them hard to see among the branches.

Sloths turn green in the rainy season from algae that grows in their fur. This helps the sloth blend into the rain forest and protects it from large birds of prey, such as the harpy eagle, and big cats. Sloth fur also provides a home to a variety of invertebrates (animals without backbones) — some of which are found nowhere else on earth. A single sloth can host more than 100 moths and other insects within its fur.

Sloths get little energy from their diet, feeding mostly on leaves. Two-toed sloths may also eat fruits and flowers. They need relatively little food and have a lower rate of metabolism than do other mammals of similar size. Metabolism is the process by which living things turn food into energy. In order to save energy, sloths do not regulate their body temperature like other mammals. They have a lower body temperature than most mammals, which varies with the environmental conditions.

A sloth can take up to 30 days to digest a single leaf. As a result, they have a constantly full stomach. Sloths climb down to the forest floor to defecate (eliminate wastes) about once a week. They can lose up to a third of their body weight in one sitting. Sloths are surprisingly good swimmers. During the rainy season they can swim about three times faster than they can move on the ground.

Although commonly grouped together, the two types of sloths are actually very different animals with very different lifestyles. Two-toed sloths are slightly larger, more active, have a broader diet, and are generally faster-moving than the three-toed sloth. They have brown hair with a long, pinkish, piglike snout. Three-toed sloths have gray hair, a white face and a dark mask around the eyes. Two-toed sloths are primarily active at night, while three-toed sloths are active throughout the day and night. Although almost all mammals possess seven cervical (neck) vertebrae as standard, sloths are one of the few mammals that do not. Two-toed sloths retain only five to seven cervical vertebrae, while three-toed sloths have eight or nine. This unusual trait enables three-toed sloths to turn their head through 270 degrees. This allows them to look for predators and to see the world right side up, while hanging upside down. Sloths can live up to about 30 years.