Giant Cat Found Lounging Among Archaeological Wonders

Wednesday, October 21st, 2020

In October 2020, archaeologists carrying out maintenance work discovered this giant geoglyph (ground etching) of a cat at the site of the famous Nazca Lines in Peru.

Credit: Jhony Islas, Peru’s Ministry of Culture

This month, archaeologists discovered a catlike figure carved into a hillside in Nazca, Peru. Archaeologists are people who study the remains of past human cultures. The cat is the latest geoglyph (ground etching) to be found in a region famous for its giant designs. The Nazca people marked into the ground these designs, also called the Nazca lines. The Nazca were a Native American culture that lived as early as 100 B.C. to A.D. 800 in the coastal desert of what is now southern Peru. Drawn centuries before such other famous cats as Garfield and the Chesire Cat, this catlike geoglyph illustrates the timeless appeal of our feline friends.

The catlike image in Nazca has pointy ears, round eyes, and a striped tail. It is also engaged in a favorite cat pastime—lounging. Its long body stretches 40 yards (37 meters) on the hillside. The geoglyph is said to date from 200 B.C. to 100 B.C.—making it a lot of cat years old. The cat is believed to be older than the other geoglyphs that have been discovered at Nazca over the years. Archaeologists came across the etching while they were remodeling a section of the hill.

The Nazca made the geoglyphs by removing surface stones and piling them along the edges of the designs. Removing the dark rocks exposed the bright sand beneath. The designs have lasted for centuries in the desert environment, with little rain or wind to wear them away. The geoglyphs can only be seen in full from the air.

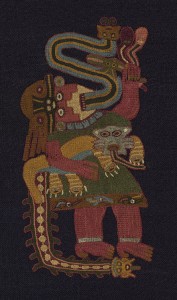

Many of the geoglyphs form the outlines of gigantic animals and plants. They include figures of a killer whale, a lizard, a monkey, and a spider. More common are geometric forms, including spirals, straight lines, trapezoids, and triangles. Some of the lines appear to spread outward from small hills, like the spokes of a wheel. The lines stretch for miles or kilometers across the desert. Platforms lie near the bases of many of the trapezoids.

In 1994, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) declared the Nazca lines a World Heritage Site. UNESCO gives this designation to areas of unique natural or cultural importance.

Scholars believe that the Nazca lines had several functions. Investigations by scientists indicate that people gathered and walked on the lines. Scholars think that people placed offerings on platforms around the shapes to encourage the nature spirits to provide rain for their crops. The animal designs symbolized the essence of the nature spirits, whereas some of the geometric lines led pilgrims to ritual centers.