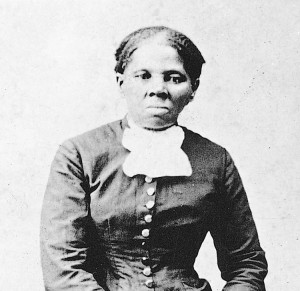

Tubman To Be Honored on Twenty

Wednesday, February 17th, 2021United States President Joe Biden has promised to accelerate a planned redesign of the $20 bill, to feature the abolitionist (anti-slavery activist) Harriet Tubman (1820?-1913). As it is now, the bill features a portrait of former president Andrew Jackson (1767-1845) on the front and a picture of the White House on the back. Jackson’s portrait will be replaced by a portrait of Tubman, a Black woman who helped hundreds of enslaved people in the United States escape to freedom.

In 2016, Secretary of the Treasury Jacob J. Lew proposed that Tubman be featured on the bill. But, the administration of President Donald J. Trump, who became president in 2017, postponed the change indefinitely. President Biden’s Treasury Department is determining how to speed up the process of adding Tubman to the $20 bill. Putting Tubman on the bill is intended to both celebrate and reflect the diversity of the United States.

Harriet Tubman was a famous leader of the underground railroad. The underground railroad was a secret system of guides, safehouses, and pathways that helped people who were enslaved escape to the northern United States or to Canada. Admirers called Tubman “Moses,” in reference to the Biblical prophet who led the Jews out of slavery in Egypt.

Tubman was born into slavery on Maryland’s Eastern Shore some time around 1820. Her name was Araminta Ross. She came to be known by her mother’s name, Harriet. Her father taught her a knowledge of the outdoors that later helped her in her rescue missions. When Harriet was a child, she tried to stop a supervisor from punishing another enslaved person. The supervisor fractured Harriet’s skull with a metal weight. Because of the injury, Harriet suffered blackouts. She interpreted them as messages from God. She married John Tubman, a free Black man, in 1844.

Harriet Tubman, acting alone, escaped from slavery in 1849. After arriving in Philadelphia, she vowed to return to Maryland and help liberate other people. Tubman made her first of 19 return trips shortly after Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. This law made it a crime to help enslaved runaways.

Tubman became a conductor (guide) on the underground railroad. She carried a gun and promised to use it against anyone who threatened the success of her operation. She was assisted by white and free Black abolitionists. She also got help from members of a religious sect known as the Quakers. On one rescue mission, she and a group of fugitives boarded a southbound train to avoid suspicion. On another mission, Tubman noticed her former master walking toward her. She quickly released the chickens she had been carrying and chased after them to avoid being recognized. In 1857, Tubman led her parents to freedom in Auburn, New York. Slaveowners offered thousands of dollars for Tubman’s arrest. But they never captured her or any of the 300 enslaved runaways she helped liberate before the American Civil War (1861-1865).

Tubman continued her courageous actions during the Civil War. She served as a nurse, scout, and spy for the Union Army. During one military campaign along the Combahee River in South Carolina, she helped free more than 750 enslaved people. After the war, Tubman became the subject of numerous biographies. Upon returning to Auburn, she spoke in support of women’s rights. She established the Harriet Tubman Home for elderly and needy Black Americans. She died on March 10, 1913.

The people of Auburn erected a plaque in Tubman’s honor. The United States Postal Service issued a postage stamp bearing her portrait in 1978. The Harriet Tubman National Historical Park, in Auburn, includes Tubman’s home, the residence she created for elderly Black Americans, and the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church she raised funds to build. The historical park, which is operated by the National Park Service, opened in 2017. Also in 2017, a museum at the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historical Park opened to the public. The national historical park, created by Congress in 2014, includes sites in Dorchester, Caroline, and Talbot counties on Maryland’s Eastern Shore.