Black History Month: Grammy Winners

Monday, February 27th, 2023

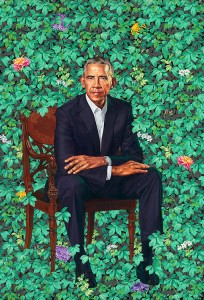

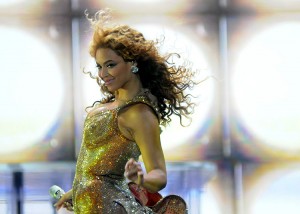

Beyoncé is a popular American singer and actress. She first gained fame as a member of the singing group Destiny’s Child. In the early 2000′s, Beyoncé established herself as a successful solo performer. Credit: © Shutterstock

February is Black History Month, an annual observance of the achievements and culture of Black Americans. This month, Behind the Headlines will feature Black pioneers in a variety of areas.

Many notable artists graced the stage at the 2023 Grammy Awards on February 5th, 2023, but Beyoncé and Viola Davis hit the headlines starting Black History Month with shiny awards. American singer and actress Beyoncé broke the record for the most Grammy Awards won by any artist, with 32 awards. American actress Viola Davis won a Grammy Award for her audiobook Finding Me, published in 2022. This Grammy secured Davis as one of the relatively few actors who have won Academy, Emmy, Grammy, and Tony awards. Only 18 people have won all four awards to become what the industry calls E.G.O.T.s. Other big winners include American rap musician and songwriter Kendrick Lamar who won best rap performance, song, and album. American rap artist, singer, and musician Lizzo won the record of the year for “About Damn Time” (2022).

Beyoncé’s career is more than inspiring. Beyoncé Giselle Knowles was born on Sept. 4, 1981, in Houston, Texas. At the age of 9, she began singing with an all-girl group called Girl’s Tyme. The group changed its name often before the members settled on Destiny’s Child and recorded a number of hit songs. In the early 2000’s, Beyoncé established herself as a successful solo performer.

Beyoncé had begun performing on her own while still singing with Destiny’s Child. Her first album, Dangerously in Love (2003), was an international hit. It was followed by the hit albums B’Day (2006), I Am…Sasha Fierce (2008), 4 (2011), Beyoncé (2013), Lemonade (2016), and Renaissance (2022). Her most popular singles include “Crazy in Love” (with rap singer Jay-Z, 2003); “Irreplaceable” (2006); “Single Ladies (Put a Ring on It)” (2008); “Drunk in Love” (also featuring Jay-Z, 2013); “Formation” (2016); and “Break My Soul” (2022). In 2008, she married Jay-Z. The couple released their first joint album, Everything Is Love, in 2018. In 2018, Beyoncé became the first Black woman to headline (be engaged as a leading performer at) the annual Coachella Valley Music and Arts Festival held in Indio, California.

As an actress, Beyoncé made her debut in the made-for-TV musical motion picture Carmen: A Hip Hopera (2001). She also appeared in the movies Austin Powers in Goldmember (2002), Dreamgirls (2006), Cadillac Records (2008), and Obsessed (2009). Beyoncé provided her voice for a character in the animated feature film Epic (2013). She also voiced the lioness character Nala in The Lion King (2019), a computer-animated remake of the 1994 animated feature film The Lion King.

Viola Davis has received more varied awards compared to Beyoncé. Davis became known for her intense performances. She also became known as an activist for greater inclusion, particularly of African Americans, in the movie and theater industries.

Davis was born on Aug. 11, 1965, in rural Saint Matthews, South Carolina. In 1988, she received a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in theater from Rhode Island College, in Providence, Rhode Island. In 1993, she received a certificate in acting from the Juilliard School in New York City, New York.

Davis got her first big acting break in 1995 in American dramatist August Wilson’s play Seven Guitars. Her bold performance as the character Vera Hedley earned her the first of many Tony Award nominations. Davis made her first motion-picture appearance in the drama The Substance of Fire (1996). She gained widespread recognition in the film Doubt (2008), in which she played a mother fighting for justice for her son. Davis’s other notable movies include The Help (2011), Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (2020), and The Woman King (2022).

How did Davis secure E.G.O.T. status? She won Tony Awards in 2001 and 2010, for her acting in the plays King Hedley II and Fences, respectively. Both plays were written by August Wilson. In 2015, Davis became the first Black woman to win the Primetime Emmy Award for outstanding lead actress in a drama series, for her performance in the TV series “How to Get Away with Murder” (2014-2020). In 2017, she won the Academy Award for best supporting actress for her role in the movie Fences (2016). And in 2023, Davis won a Grammy Award for the audiobook of her memoir Finding Me, published in 2022.