100 Years Ago: Tulsa Race Riot

Tuesday, June 1st, 2021

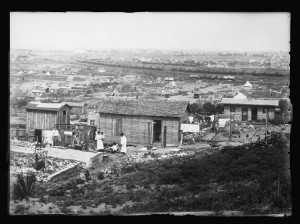

A thriving Black neighborhood known as “Black Wall Street” lies in ruin following the Tulsa race riot of 1921.

Credit: Library of Congress

May 31, 2021, marked 100 years since the start of the Tulsa race riot of 1921. It was one of the deadliest acts of racial violence in United States history.

From May 31 to June 1, 1921, groups of armed white men attacked Black residents in Tulsa, Oklahoma. The riot began after white vigilantes gathered to lynch (put to death without a lawful trial) a Black man who had been accused of attacking a white woman. The riot probably caused about 300 deaths and destroyed Tulsa’s Black business district.

On May 30, 1921, Dick Rowland, a 19-year-old Black shoe shiner, entered an elevator in the Drexel Building in downtown Tulsa. He encountered Sarah Page, a 17-year-old white elevator operator. What occurred next is unclear. Many historians believe that Rowland may have either stepped on Page’s foot or tripped and grabbed Page’s arm to steady himself. Page screamed. A clerk from a nearby store, assuming that the girl had been the victim of an assault, called police. Rowland fled the scene and was arrested the next day.

Newspaper accounts and rumors about the incident led to widespread talk of lynching. On the evening of May 31, hundreds of white people, including many armed men, gathered near the courthouse where Rowland was held. Groups of armed Black men—many of them veterans of World War I—then arrived at the scene. They offered their services to the sheriff to help protect Rowland, but their offers were refused.

At around 10 p.m., shots were fired during a commotion near the courthouse. The Blacks who had gathered there were outnumbered, and they retreated. They went to Greenwood Avenue—the heart of the Black business district known as “Black Wall Street.” A white mob followed.

Scattered shootings then occurred near Greenwood Avenue in the early hours of June 1. Groups of armed Blacks assembled to hold off the white mob. Many Black residents fought to protect their businesses or families, while others fled to the countryside. Law enforcement officials deputized (appointed as agents of the law) hundreds of members of the mob. Members of the Oklahoma National Guard—all of whom were white—gathered near boundaries of Black and white neighborhoods. Among some whites, rumors attributed the violence to a “Negro uprising.” The mob grew to more than 5,000 white men.

Around 5 a.m., a whistle sounded, and thousands of armed white men marched into the Black business district. They burned and looted homes and businesses. National Guardsmen led thousands of Blacks at gunpoint to makeshift detention centers. Many who resisted were shot. Police did little to stop the arson and violence, and they spent most of their resources protecting white neighborhoods. In many instances, local members of the state National Guard joined in the attacks. Black eyewitnesses recalled white pilots firing on Black neighborhoods from airplanes above.

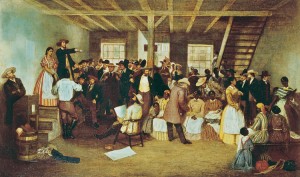

Thousands of armed white men burned and looted Black homes and businesses during the riot.

Credit: Library of Congress

Around 9 a.m., members of a National Guard regiment from Oklahoma City arrived in Tulsa. Locals called them the “state troops.” Order was restored around 11:30 a.m., when Governor James B. A. Robertson declared martial law (emergency military rule) in Tulsa County. By the time the riot ended, more than 1,200 structures—nearly the entire “Negro Quarter”—had been destroyed by fires.

There is documented evidence of at least 40 deaths in the Tulsa riot. Of this number, about two-thirds were Black. However, many historians estimate that around 300 people were killed. Some unidentified Black victims may have been interred in mass graves.

Authorities never brought criminal charges against Rowland. Authorities also brought no charges against white rioters. Neither the City of Tulsa nor insurance companies compensated Black property owners for losses. The Greenwood business district was eventually rebuilt, but many of its residents remained homeless for months.

Newspapers reported on the riot in the days and weeks after the event. Over time, however, the incident received little coverage. The riot was omitted from most Oklahoma history books and classroom lessons.

Blacks displaced by the neighborhood’s destruction line up outside a refugee camp at the Tulsa fairgrounds.

Credit: Library of Congress

In 1997, state officials formed the Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. The commission released an extensive report about the event in 2001. Tulsa’s John Hope Franklin Reconciliation Park commemorates the victims of the riot. The park, named for a leading Black scholar whose own father survived the riot, officially opened in 2010.