Black History Month: Honoring Buck O’Neil, Belated, but “Right on Time”

Friday, February 25th, 2022

Buck O’Neil former player in the Negro Baseball league is honored at a Brooklyn Cyclones baseball game.

Credit: © Bruce Cotler, Globe Photos/ZUMA/Alamy Images

February is Black History Month, an annual observance of the achievements and culture of Black Americans. This month, Behind the Headlines will feature Black pioneers in a variety of areas.

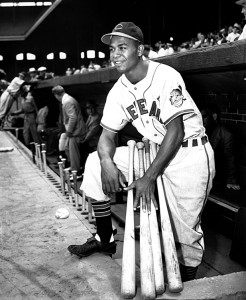

Baseball legend Buck O’Neil was the thread that connected Josh Gibson and Babe Ruth with Lionel Hampton and Ichiro Suzuki. He remains among the most celebrated and important figures in the history of baseball. O’Neil left a lasting impact on the sport as a skilled player, a knowledgeable manager, a shrewd judge of talent, a passionate promoter, and a gifted storyteller.

Major League Baseball (MLB) failed to appreciate Buck O’Neil in a timely fashion. It denied him the chance to play or manage in the league because he was Black. But the sport’s ultimate recognition is finally coming to him, albeit too late for him to enjoy it. In December of last year, the Early Baseball Committee voted to admit O’Neil into the Hall of Fame. He will be formally inducted in July.

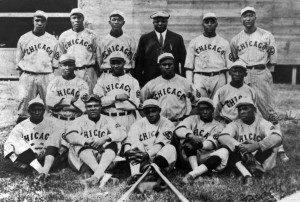

John Jordan O’Neil, Jr., was born Nov. 13, 1911, in Carrabelle, Florida, on the Gulf Coast. His father played baseball and introduced him to the game. Around 1920, the family moved to Sarasota, near the spring training facilities of several MLB teams. As a youth, O’Neil watched such players as Babe Ruth prepare for the season. His family would also take him to Negro league games. Negro leagues were professional baseball leagues formed for Black players, who were barred from playing alongside white players because of racial segregation.

As a teenager, O’Neil worked in the fields harvesting celery. He was prohibited from attending the segregated high school in Sarasota. He received high school and college instruction from Edward Waters College (now Edward Waters University), a historically Black college in Jacksonville.

In 1934, O’Neil began playing for small Negro league teams. O’Neil got the nickname “Buck” after being mistaken for a Negro league team owner named Buck O’Neal. O’Neil joined the Kansas City Monarchs in 1938. His sure fielding at first base and high batting average helped the Monarchs to win four consecutive Negro American League pennants from 1939 to 1942.

At the time, Kansas City, Missouri, was one of the hubs of Black culture. O’Neil and many of his teammates were obsessed with jazz. They rubbed elbows with such jazz greats as Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Lionel Hampton.

In 1943, O’Neil was drafted into the United States Navy to serve in World War II (1939-1945). He returned to the Monarchs after the war and was named player-manager in 1948. A player-manager manages a baseball team while also playing for the team.

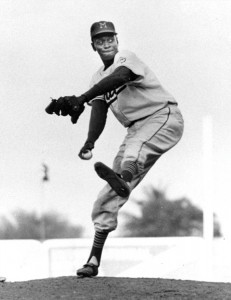

Jackie Robinson had broken MLB’s color barrier the year before, and MLB clubs were signing star players away from Negro leagues teams. The loss of talent caused many Black baseball fans to lose interest in the Negro leagues. To keep the Monarchs in business, O’Neil sought out talented young Black players, signed them, and sold their contracts to MLB teams. He signed a young Ernie Banks on the recommendation of fellow Negro leagues legend Cool Papa Bell.

In 1955, O’Neil was hired as a scout by the MLB Chicago Cubs. He specialized in signing players from the remaining Negro leagues teams and Black players from the South. He scouted future Hall-of-Famers Lou Brock, Lee Smith, and Billy Williams.

In 1962, the Cubs named O’Neil a coach, making him the first Black coach in MLB history. At the time, the Cubs were utilizing a “college of coaches” approach, in which a group of men shared coaching duties throughout the season. O’Neil was given the impression that he might get a chance to manage the team.

During a game that season, a series of ejections of coaches made O’Neil the logical choice to fill in as the third-base coach. He would have become the first Black on-field coach in MLB history. But another coach came in to coach third instead. Years later, O’Neil learned that Cubs coach Charlie Grimm had told the other coaches that O’Neil was never to coach in the field or manage. O’Neil was certain that this exclusion was racially motivated. O’Neil returned to scouting in 1964. In 1988, he became a scout for the Kansas City Royals.

Later in life, O’Neil campaigned to raise public awareness of the Negro leagues. In 1990, he helped establish the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City. O’Neil was featured prominently in the documentary miniseries “Baseball” (1994) by the American filmmaker Ken Burns. He regaled audiences with stories of such Black baseball stars as Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson. The work served to introduce younger generations of baseball fans to the players of the Negro leagues.

O’Neil’s warmth, love of baseball, and gift for storytelling won him friends and admirers wherever he went. Star hitter Ichiro Suzuki met O’Neil early in his MLB career and sought him out whenever he traveled to Kansas City. After O’Neil’s death, Suzuki donated a large sum to the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum.

O’Neil lobbied to get Negro leagues players elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. But in 2006, when 17 Negro leagues players and executives were inducted, O’Neil was not selected. The Hall of Fame asked O’Neil to speak during the induction anyway, since none of the 17 honorees were still living. O’Neil agreed and gave a speech praising the new Hall-of-Famers during the induction ceremony.

Despite O’Neil’s magnanimity, those close to him speculated that the snub broke his heart. O’Neil died on Oct. 6, 2006, just two months after the ceremony. It took 15 more years before O’Neil was finally inducted.

In July, O’Neil will take his rightful place next to the other legends of the game, many of whom he met, played against, or mentored. One of his own sayings fits this belated honoring of one of baseball’s greatest treasures: “Waste no tears for me. I didn’t come along too early—I was right on time.”