The Ocean Plastic Plague

September 21, 2018

In the Pacific Ocean, floating plastic pollution has collected into a giant area of marine debris known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP). Marine debris consists of garbage dumped directly into the ocean or carried there by waterways. Such debris can injure animals or make them ill. It can also poison and bury marine habitat. The GPGP, also called the Pacific trash vortex, spans an astounding 600,000 square miles (1.6 million square kilometers) of ocean surface—an area more than twice the size of Texas and nearly three times the size of France.

A member of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) helps disentangle an albatross chick from plastic debris in the northwestern Hawaiian islands. Credit: Ryan Tabata, NOAA

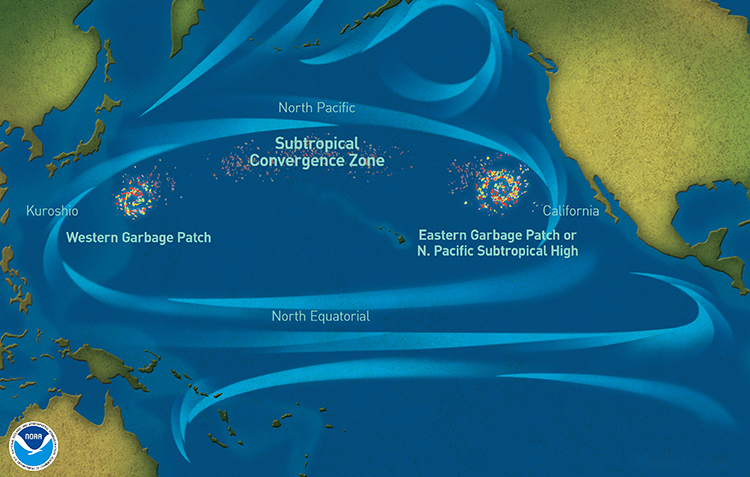

The GPGP is actually two large fields of marine debris, a western patch near Japan and an eastern patch near Hawaii. The fields are linked by a convergence zone where warm South Pacific waters meet cooler Arctic waters. There, currents and winds carry garbage from one patch to the other. Circular currents move clockwise around the patches, creating a massive vortex that keeps the debris from scattering to other parts of the planet. Unfortunately, all ocean waters have similar pollution problems, and the ocean plastic plague is not limited to the vast Pacific.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch includes two general areas of massed marine debris collected and held in place by ocean currents. Credit: NOAA Marine Debris Program

The GPGP contains an estimated 1.8 trillion pieces of fishing nets, glass, light metals, ropes, and other discarded rubbish. Most GPGP debris is washed out to sea from Asia and North America. Other debris is left behind by boaters, oil rigs, and cargo ships. The majority of this debris is made of plastic, and it gathers in large patches because it floats and much of it is not biodegradable. Most plastics do not wear down or decompose; they simply break into tinier and tinier pieces. The GPGP is visible in large swaths on the ocean surface, but much of it exists as microplastics in what appears to be cloudy or milky-colored water. Oceanographers and ecologists recently learned that only a fraction of marine debris floats near the surface, meaning that the deeper waters and sea floors beneath the GPGP are also heavily polluted.

Plastics in particular are a problem because of their omnipresence: they are simply everywhere. Most plastic objects are easy to spot, but plastics exist where you might not expect them: the synthetic chewy polymer in gum, the microbeads in soaps and gels, and even the microfibers of fleece or nylon clothing. Plastics are cheap to manufacture, so cheap, in fact, that many plastics are only used once. Such single-use plastics are the greatest threats to the world’s oceans. People typically use plastic bags, coffee stirrers, forks and spoons, straws, soda and water bottles, and food packaging only once and then throw them away. These items end up in landfills, in lakes and rivers, and in the oceans, and they do harm everywhere. Most of these items can be recycled, but only about 10 percent of plastic is ever reused. Scientists estimate that humans discard about 300 million tons (275 million metric tons) of plastic every year. Of that amount, some 9 million tons (8.1 million metric tons) finds its way into the world’s oceans.

Plastic pollution has a dire effect on marine wildlife, killing hundreds of thousands of fish, sea birds, sea turtles, seals, whales, and other smaller animals each year. Larger animals become entangled in plastic, trapping them or hindering their movement, and they drown or die of starvation. Sea turtles eat plastic bags, mistaking them for their favorite food, jellyfish. The bags suffocate the turtles or kill them by blocking their digestive systems. Sea birds such as albatrosses often mistake plastic resin pellets for fish eggs and feed them to chicks, which then starve or die of ruptured organs. Clouds of microplastics can kill by blocking sunlight: phytoplankton and other types of algae (a large base of the ocean food chain) depend on photosynthesis to survive. Microplastics also effect small fish and carnivorous plankton that mistakenly eat the synthetic particles: the animals either die or pass the plastic up the food chain. Researchers have found high numbers of plastic fibers inside food fish sold at markets—so yes, people too end up eating indigestible and often toxic plastic.

So there is an ocean plastic plague out there, and it is spreading every day: what is being done about it? At sea, unfortunately, little is happening. The GPGP and many other ocean garbage patches around the world lie in international waters. A nation’s territorial waters extend only 12 nautical miles (14 miles or 22 kilometers) from the coast. Most nations observe this limit to regulate commercial fishing, navigation, shipping, and use of the ocean’s natural resources. While some nations claim territorial waters much farther out than 12 nautical miles, none wants the responsibility or expense of cleaning the pollution that collects out there. International waters are exploited and heavily trafficked, but garbage patches are largely ignored beneath the prows of money-making ships.

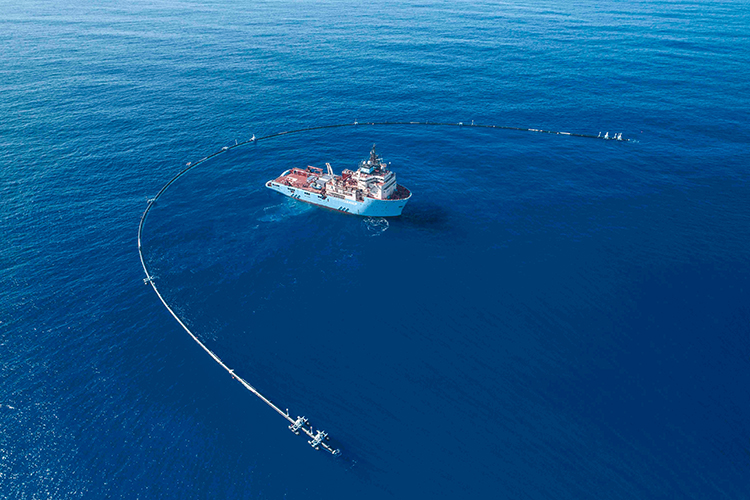

A tugboat deploys The Ocean Cleanup’s first ocean-sweeping floater to collect plastic marine debris on Sept. 15, 2018. Credit: The Ocean Cleanup

Individual efforts are helping, however. Dutch inventor Boyan Slat recently founded The Ocean Cleanup, an organization that has developed an ocean-sweeping floater to collect plastic garbage. The floater—made from a durable, recyclable plastic called high density polyethylene (HDPE)—is a 1,000-foot- (600-meter- ) long horseshoe that collects plastics in its mouth and in screens that drape beneath the surface. The screens are made from a tightly woven textile impenetrable to marine life, preventing animals from becoming ensnared. The plastics are collected, extracted, and either recycled, resold, or disposed of properly. The floaters will be placed in low-trafficked sea zones, illuminated and equipped with radar and Global Positioning System (GPS) beacons to avoid collisions with ships. The first of these ocean-sweeping floaters began Pacific sea trials in September 2018, and The Ocean Cleanup hopes to have a fleet of 60 such cleaning systems by 2020. The lofty goal is to reduce the Great Pacific Garbage Patch by 50 percent by 2025.

Other organizations doing what they can to help include the Plastic Pollution Coalition and the Plastic Oceans Foundation. Other inventive forms of cleanup include introducing plastic-eating bacteria (a slow cure that could create other problems) and small scale “SeaBins” that float in harbors and filter out floating garbage.

As Benjamin Franklin famously said, however, an ounce of prevention is worth of a pound of cure. Stopping the ocean plastic plague—and all other forms of pollution—depends on our habits and behaviors at home. Governments must encourage recycling and develop better waste management systems. Industry must switch to more environmentally friendly plastics capable of natural decomposition. Fishing crews can help by collecting plastic caught in their nets and returning it to shore for processing. Individuals can help by reducing the use of disposable plastics and products with plastic microbeads or microfibers. If plastics must be used, recycle or reuse whenever possible. And, as always and with everything, never litter.