Sauropods Selected Steamy Savannas and Shunned Snowy Settings

Thursday, March 10th, 2022

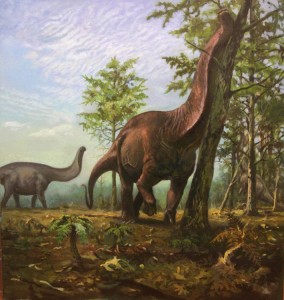

Sauropods were the most spectacular of the dinosaurs. Their long necks supported small heads that took in needles and leaves. Despite such a nutrient-poor diet, they reached sizes and lengths unparalleled in any other terrestrial (land-dwelling) animals. How—and why—did they get so large? A recent study may have discovered a lead to unraveling the physiology of these amazing animals.

Over tens of millions of years, the arrangement of the continents has shifted through the action of plate tectonics. Geologists can trace how a location has moved over the face of Earth to determine its paleolatitude. The paleolatitude is the position of a point on the Earth’s surface in relation to the equator at a time in the distant past. Both latitude and paleolatitude are measured on a scale of 0° (the equator) to 90° (the poles). Higher latitudes experience cooler temperatures and less sunlight in winter.

Dinosaurs reigned during the Mesozoic Era—a time of warmer climates. Despite the planet being largely ice-free, regions near the poles still faced cold winters and weeks or months without sunlight. Nevertheless, dinosaurs have been found at high paleolatitudes, including in Antarctica and Alaska. At least some of these dinosaurs remained there through the winter.

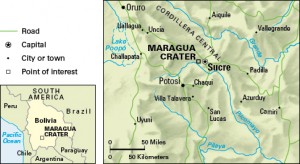

Sauropod fossils, however, are conspicuously absent from these polar locations. No sauropod fossil has been discovered from a paleolatitude higher than about 65°. Instead, these chilly climates were strictly occupied by meat-eating theropods and some plant-eating dinosaurs called ornithischians.

Some paleontologists (scientists who study prehistoric life) suspected the absence of fossils suggest that sauropods preferred warmer climates. But others thought that sauropods might not have fossilized well near the poles for some reason, or that the fossils are still waiting to be discovered.

A team led by Alfio Alessandro Chiarenza of the University of Vigo in Spain analyzed the paleolatitude of all the places where sauropod fossils have been found. The team published their findings last month in the scientific journal Current Biology. They determined that the absence of sauropods at high paleolatitudes was not due to incomplete sampling. Chiarenza’s team used models of the Mesozoic climate and found that sauropods preferred savanna-type habitats. Sauropod ranges were tightly constrained by the lowest predicted temperature.

Why didn’t (or couldn’t) sauropods brave the cold? They might have cooled down too quickly, despite their massive sizes. Many theropods—and possibly some ornithischians—had downy or hairlike feathers that could be used to keep them warm. Sauropods lacked any such insulation. Furthermore, a sauropod’s long necks and tails might have lost heat quickly when exposed to bitter-cold winds.

Sauropods buried their eggs in the earth to keep them at a stable temperature. But this method probably would not have kept the eggs warm enough in cold climates. In contrast, theropods sat on their eggs and ornithischians covered their eggs in rotting plants. Both of these approaches could keep the eggs warm even in cold climates.

Chiarenza’s team proposes that sauropods did not possess as high of a metabolism as theropods and ornithischians. Historically, scientists have classified animals as endothermic (“warm-blooded”) or ectothermic (“cold-blooded”). Endothermic animals tend to produce more of their own body heat, while ectothermic animals tend to rely more on their environment for heat. This is a false division, since every animal is somewhat reliant on its environment for heat. But animals classified as endothermic can usually survive in cooler temperatures. Reptiles, the classic endotherms, are concentrated near the equator.

In many ways, this makes a lot of sense. A lower metabolism would have enabled sauropods to survive on less food. Their huge size would cause them to lose less heat to their environment, much like a well-insulated building. Growing evidence suggests that the ancestor of dinosaurs and crocodilians (a group of reptiles) had a high metabolism, but crocodilians “slowed down” when dinosaurs took over most environmental niches. A similar changed might have occurred in sauropods as well, enabling them to attain colossal sizes. Sometimes slow and steady wins the race.