Indigenous Peoples’ Day Spotlight: Nicole Mann

Monday, October 9th, 2023

Nicole Aunapu Mann became the first Indigenous American woman in space in October 2022 aboard NASA’s SpaceX Crew-5 mission to the International Space Station.

Credit: NASA

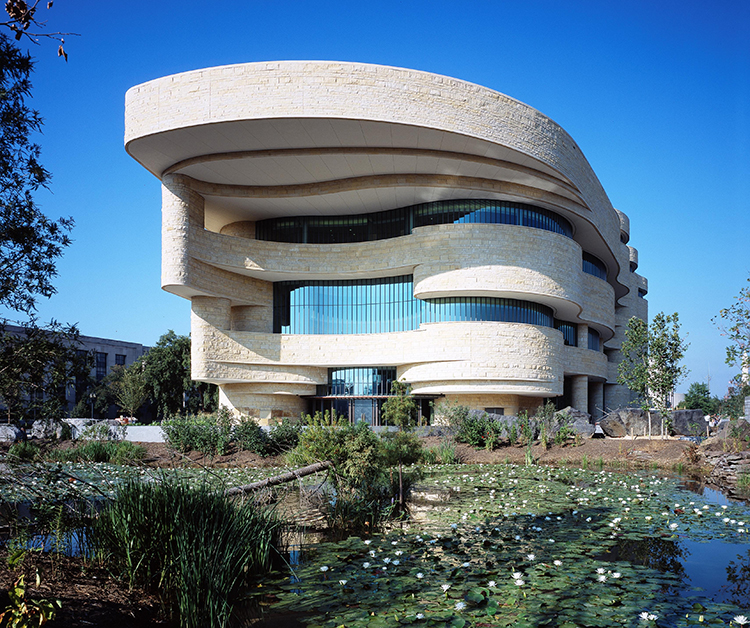

Today is Indigenous Peoples’ Day in the United States! Indigenous Peoples’ Day celebrates and honors Indigenous Americans’ history and culture. On October 5, 2022, Mann became the first Indigenous (native) American woman in space. Nicole Aunapu Mann is an American astronaut and Marine Corps test pilot. Mann and three other astronauts launched on National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) SpaceX Crew-5 mission to the International Space Station (ISS). While aboard the ISS, Mann will served as flight engineer. Mann and the crew safely landed back on Earth on March 11, 2023. Mann is a member of the Wailacki people of the Round Valley Indian Tribes. The Round Valley Indian Tribes is a confederation of tribes designated to the Round Valley Indian Reservation in Mendocino County, California.

In 2013, the NASA chose Mann to be an astronaut. Mann completed astronaut training in July 2015. She led the development of the Exploration Ground Systems (EGS) launch facility, the Orion crewed spacecraft, and Space Launch System (SLS), built to carry the Orion craft into space. NASA selected Mann to serve as mission commander on NASA’s SpaceX Crew-5 mission on the Crew Dragon capsule en route to the International Space Station. SpaceX is a private company that owns and operates the rocket and spacecraft used in the mission. A Falcon 9 rocket was scheduled to launch the mission’s Crew Dragon capsule.

Mann joined the United States Marine Corps in 1999 as a second lieutenant. She reported to the Naval Air Station in Pensacola, Florida, for flight training in 2001. Mann became a Navy pilot in 2003 and began her operational flying career in 2004. Mann deployed twice to Afghanistan and Iraq, completing 47 combat missions. After her deployments, she completed Navy Test Pilot School and served as a test pilot for many types of naval aircraft.

Nicole Victoria Aunapu was born in Petaluma, California, on June 27, 1977. She enrolled in the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, in 1995. Mann earned a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering in 1999. She completed a master’s degree in mechanical engineering from California’s Stanford University in 2001. In 2009, she married Navy pilot Travis Mann.