National Museum of the American Indian

Wednesday, November 7th, 2018November 7, 2018

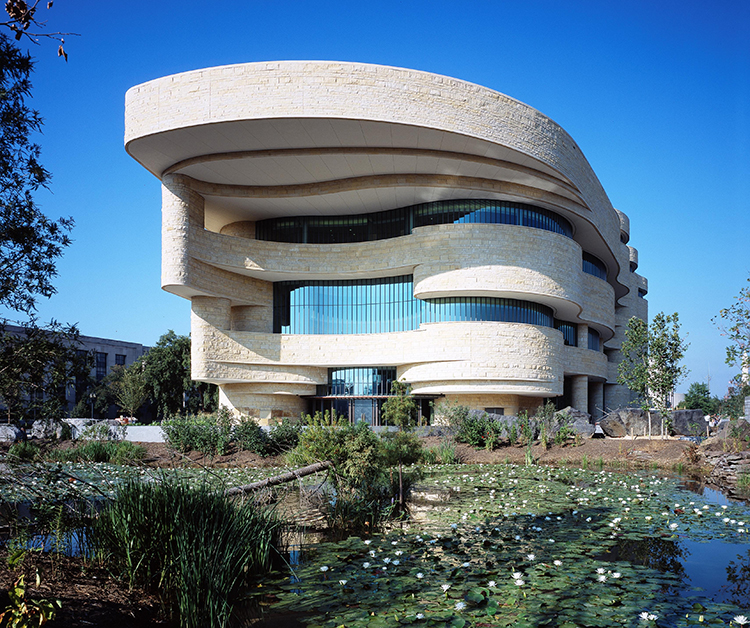

November is Native American Heritage Month in the United States. To celebrate the month, World Book looks at the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, D.C. The NMAI is devoted to the histories and cultures of the native peoples of the Americas. The museum works in cooperation with Native American communities to present objects, exhibits, and artworks of historical significance. The museum’s collections also showcase modern Native American arts and cultures. The NMAI, which is part of the Smithsonian Institution, has three facilities: the main museum campus on the National Mall; the George Gustav Heye Center in New York City; and the Cultural Resources Center in Suitland, Maryland.

The National Museum of the American Indian is devoted to the history and culture of the native peoples of North, Central, and South America. The museum’s building, in Washington, D.C., has smooth, rounded forms that were inspired in part by windswept rock formations. Many Native American architects and designers worked on the design. Credit: Pixabay

George Gustav Heye, an American art collector, established the Museum of the American Indian in New York City in 1916. In 1989, the United States Congress created the NMAI and moved Heye’s collection to the Smithsonian. The museum opened in 2004.

November is Native American Heritage Month in the United States. Credit: © Native American Heritage Month

This November, the NMAI is featuring an exhibit called “Patriot Nations: Native Americans in Our Nation’s Armed Forces.” The exhibit details the sometimes-conflicted participation of Native Americans in the U.S. military since the days of the American Revolution (1775-1783). It also details the new National Native American Veterans Memorial that will soon grace the museum’s grounds.

Native American Heritage Month began as American Indian Day in 1916, when certain states began honoring Native Americans with a day each May. President George H. W. Bush approved a joint resolution of Congress designating the first Native American Heritage Month in November 1990. The month honors all the native peoples of the United States, including Alaskan natives and Pacific Islanders.