Iditarod 2019

Monday, March 18th, 2019March 18, 2019

Last week, on March 13, the American musher (sled driver) Peter Kaiser won the annual Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race in Alaska. The Iditarod is the world’s most famous sled dog race. The 1,100-mile (1,770-kilometer) race starts on the first Saturday of March in Anchorage and ends in Nome. Kaiser, who is from Alaska, is the first musher of Yup’ik descent to win the race. The Yup’ik are an Inuit people native to the region.

The Iditarod is a famous sled dog race held every March in Alaska. Teams of sled dogs race from Anchorage to Nome. Credit: © Shutterstock

Kaiser’s winning race time was 9 days, 12 hours, 39 minutes, and 6 seconds—just 12 minutes ahead of the defending champion, Joar Leifseth Ulsom of Norway. (The third-place musher, Jessie Royer of Fairbanks, Alaska, brought her dog team in nearly six hours after Leifseth Ulsom, a more common time differential for such a long endurance race.) It was the first Iditarod win for Kaiser, who has raced every year since 2010.

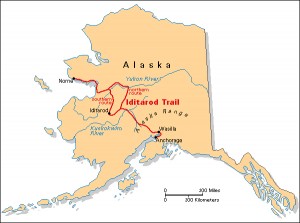

The Iditarod crosses the Alaska and Kuskokwim mountain ranges, heading northwest across the state and then north along the Bering Sea coast to Nome. The race follows a northern route in even years and a southern route in odd-numbered years. The Iditarod requires enormous endurance, both from the musher and the dogs. The race follows icy, snowy trails and typically takes about 10 to 17 days. Mushers and their dogs may train all year for the race. Both men and women compete.

Click to view larger image

The Iditarod is a famous sled dog race held every March in Alaska. Teams of sled dogs race from Anchorage to Nome on the Iditarod Trail, a dog sled mail route first used in 1910. Credit: WORLD BOOK map

At least 12 dogs and no more than 16 dogs must start the race. At least 5 dogs must finish. The dogs, usually Siberian or Alaskan huskies, are selected for speed, endurance, and courage. The sled is extremely light, but it must be strong enough to carry the weight of the musher, equipment and provisions for the race, and sick or exhausted dogs.

The current Iditarod format originated in 1973, developing from shorter sled dog races first held in 1967 and 1969. It is held on the Iditarod Trail, a dog sled mail route first used in 1910. The race also commemorates an emergency rescue mission by dog sled to get medical supplies to Nome during a diphtheria outbreak in 1925. Balto, the lead sled dog in the final leg of that mission, became a popular canine celebrity.