Native American Heritage Month: Ben Nighthorse Campbell

Thursday, November 30th, 2023

Ben N. Campbell was a member of the United States Senate from 1993 to 2005. Campbell, a Republican, represented Colorado. Before becoming a senator, Campbell had served in the Colorado House of Representatives and the U.S. House of Representatives.

U.S. Senate

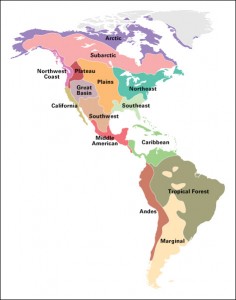

People in the United States observe Native American Heritage Month each year in November. During this period, many Native tribes celebrate their cultures, histories, and traditions. It is also a time to raise awareness of the challenges Indigenous people have faced in the past and today, along with their contributions to the United States as its first inhabitants.

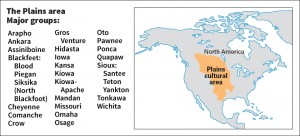

Ben Nighthorse Campbell, a Northern Cheyenne chief, was a member of the United States Senate from 1993 to 2005. He represented Colorado. When he was elected, Campbell became the first Native American person since the late 1920′s to hold a U.S. Senate seat. Charles Curtis, whose mother was part Native American, served in the Senate from 1907 to 1913 and again from 1915 to 1929. Campbell was elected as a Democrat. In 1995, he switched to the Republican Party.

As a senator, Campbell focused on such issues as water conservation and environmental preservation. He worked to protect Colorado’s water resources.

Campbell was born on April 13, 1933, in Auburn, California. His father was Northern Cheyenne, and his mother was of Portuguese descent. Campbell served in the U.S. Air Force from 1951 to 1953. He earned a bachelor’s degree from San José State University in 1957. He also attended Meiji University in Tokyo. Campbell became a judo expert and was a member of the U.S. judo team in the 1964 Olympic Games in Tokyo. During the late 1960′s and the 1970′s, he built a successful business as a jewelry designer and jewelry maker and became a resident of Colorado.

Campbell was elected to the Colorado House of Representatives in 1982. He served from 1983 until 1986, when he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. He won reelection to the U.S. House in 1988 and 1990. In 1992, he was elected to the U.S. Senate, and he took office in 1993. He was reelected in 1998.

In 2004, Campbell announced that because of concerns about his health he would not seek reelection that year to the Senate. His final term as senator ended in January 2005.