Drilling for Answers

Wednesday, March 9th, 2016March 9, 2016

Next month, in April, a deep-ocean drilling project will begin off the Yucatán coast in the Gulf of Mexico. Most such oceanic drill projects are concerned with oil exploration. This isn’t your usual drill team, however. The drillers in this case come from the International Ocean Discovery Program, the National University of Mexico, and the University of Texas. And they will be drilling into Chicxulub Crater, an impact crater formed by a giant asteroid that helped kill the dinosaurs some 65 million years ago. They won’t be looking for oil; they’ll be looking for answers.

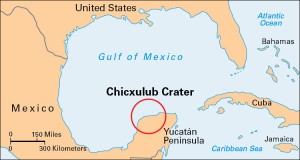

The Chicxulub Crater along the northern coast of Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula formed when an asteroid hit the earth about 65 million years ago. Debris from the impact may have led to the extinction of the dinosaurs.

Credit: WORLD BOOK map

At the end of the Cretaceous Period, dinosaurs were the dominant land animals on the planet. Other reptiles filled the seas, and birds—descendants of dinosaurs—roamed the skies. Mammals existed, but they were far smaller and less common than today. Then, an asteroid at least 6 miles (10 kilometers) wide slammed into the Yucatán Peninsula, in present-day Mexico. The impact threw up large amounts of gas and dust into the atmosphere. This material would have blotted out the sun for many years. Plants that use sunlight to make their food would have died out, followed by the animals that ate them. With no more prey animals, large carnivores starved as well.

When the dust settled, about half of all species on Earth had gone extinct. All the dinosaurs—except birds—were dead. Only a few kinds of other reptiles survived. Mammals survived too and over time evolved to become the dominant large-bodied animals on land and in the sea.

The Yucatán asteroid formed a large impact crater, which is now partly on the peninsula and partly in the Gulf of Mexico. Tens of millions of years of plate tectonics and erosion have taken their toll on the crater, and it is barely visible in satellite images today. But the mark that it left in the rocks should still be clear.

The team plans to use a drilling ship to sample rock deep beneath the ocean floor. In drilling into the crater, scientists hope the presence (or lack) of microfossils (tiny preserved remains of ancient organisms) will teach them more about the nature of the asteroid impact and how quickly life returned to the area afterwards.

The drilling evidence may also better explain how responsible the impact was for the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous Period. Most scientists agree that the asteroid did most of the damage, but others argue that other causes, such as massive volcanic activity in present-day India, were more to blame. Such extinction hypotheses are not mutually exclusive, however: it may have taken more than one disaster to knock out the dinosaurs. In fact, they may even be linked. Recent studies have suggested that the Yucatán impact caused the spike in volcanism on the other side of the globe in India. Whatever the case, the drilling team will help get to the bottom of this and other stories, as well as to the bottom of the impact crater itself!