Rosetta and the Comet

Tuesday, October 18th, 2016October 18, 2016

On September 30, a bright light of science was extinguished in the solar system. That day, the space probe Rosetta crash-landed on the comet it had been orbiting, marking the end of an ambitious mission that paid–and should continue to pay–huge dividends for astronomy.

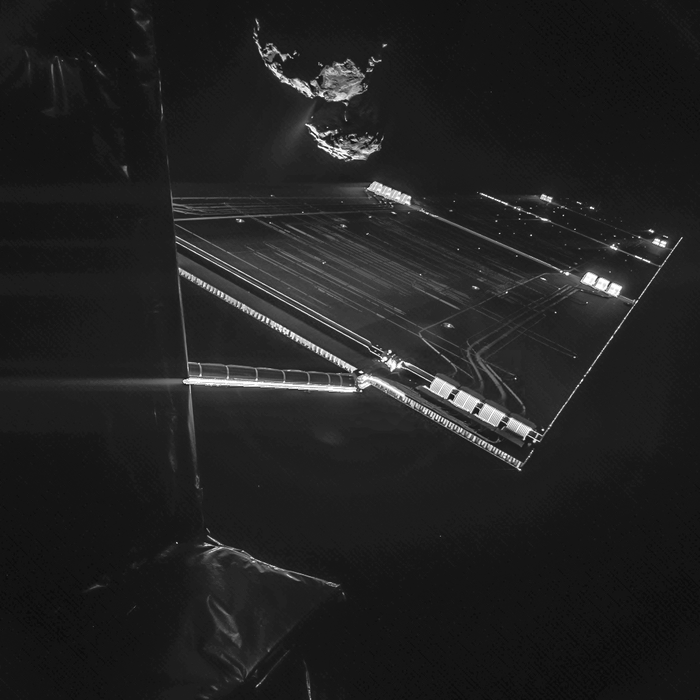

The European Space Agency (ESA) launched Rosetta on March 2, 2004. Rosetta orbited comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko from August 2014 to September 2016. Scientists think that comets preserve dust, ice, and rock from the solar system’s formation. By gathering data on a comet, therefore, Rosetta helped scientists to learn more about the solar system’s composition and history. Rosetta was named for the Rosetta stone, an inscribed rock that enabled scholars to interpret ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs. Rosetta also carried a small craft named Philae to land on the surface of the comet’s nucleus (core). Philae was named for the Philae obelisk, which also bore inscriptions that helped decipher ancient Egyptian writing.

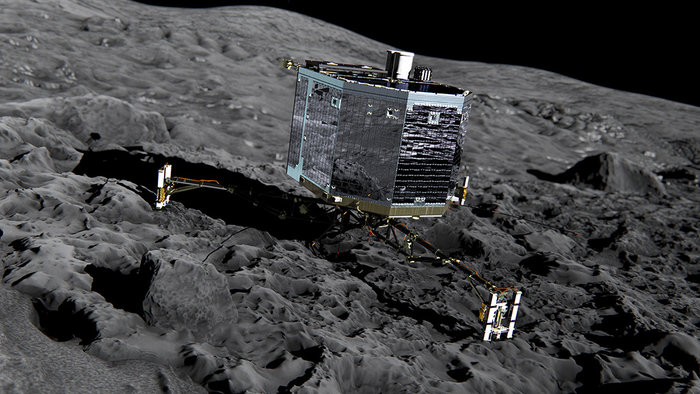

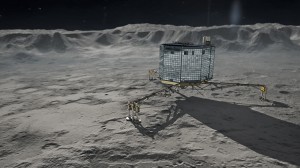

This artist’s impression shows the European Space Agency (ESA) lander Philae on the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Philae was released from the ESA probe Rosetta to gather detailed information about the comet’s structure and makeup. Credit: DLR German Aerospace Center

Rosetta overcame many difficulties to provide key insights into the history of the early universe. It was initially planned as a sample return mission to a different comet in collaboration with the United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). But because of the tragic loss of the space shuttle Challenger in 1986, NASA pulled out of the Rosetta mission, and the ESA was forced to scale it back. Many years later, in 2002, an Ariane 5 rocket failed shortly after liftoff. Rosetta was scheduled to be carried into space on the next Ariane 5 later that year. The failure grounded the Ariane 5 for many months, and mission scientists changed their target comet to 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

In 2014, when the lander Philae touched down on 67P, its landing harpoons failed to trigger. The craft bounced high into space and came down on its side in a sunless area of the comet’s nucleus. Scientists worked feverishly to conduct experiments and gather data for 57 hours before the lander’s solar-powered batteries died. Despite Philae’s loss, Rosetta continued orbiting the comet, taking photographs and collecting data. On Sept. 2, 2016, with just weeks left in the mission, Rosetta discovered the wayward Philae in the shade of a small cliff on the comet’s surface.

In spite of all the bumps along the way, Rosetta was a fabulously successful mission. It became the first spacecraft to orbit a comet, and it released the first probe to land on (rather than crash into) a comet. It returned invaluable data about the evolution of comets as they approach the sun and the history of the early solar system. Scientists are only just beginning to draw conclusions from Rosetta’s data.

Rosetta’s collision with the comet was not accidental, but had been planned by mission scientists. The highly elliptical (elongated) orbit of 67P takes it as close as 115 million miles (185 million kilometers) and as far as 530 million miles (850 million kilometers) from the sun. This creates vast and lengthy temperature changes over the course of its six-and-a-half-year orbit. These temperature extremes ravage a spacecraft’s sensors and electronic equipment. As the comet tracked back away from the sun, scientists feared that Rosetta could not survive another hibernation in the icy depths of the outer solar system. Rather than risk it, they decided to send Rosetta out in style, crashing into the comet while collecting as much data as possible. On its final descent, Rosetta studied the comet’s gas, dust, and plasma environment very close to the surface. The probe also took some harrowing high-resolution images as it plunged toward the comet.

Despite the end of Rosetta, ESA has several other important missions in progress. LISA Pathfinder plans to study gravitational waves from space. The Gaia probe is in the process of creating the most detailed map of the galaxy ever. The ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter is en route to Mars to study the planet’s atmosphere and release a lander in preparation for a future wheeled rover.