Ankylosaur Adds New Weapon to Dinosaur Armory

Thursday, March 3rd, 2022Looking at plant-eating dinosaurs is like browsing a Medieval armory. Helmets (dome-headed pachycephalosaurs), whips (sauropods), shields (Stegosaurus and ceratopsians—though those of the latter probably weren’t used for defense), spears (Stegosaurus, Triceratops), clubs, and thick armor (both ankylosaurs). Now, paleontologists (scientists who study ancient life) have added a sword to the list of prehistoric weaponry.

A team led by Sergio Soto-Acuña, a paleontology student at the University of Chile, discovered a dinosaur they named Stegouroselengassen. The dinosaur lived between 75 and 72 million years ago in what is now Patagonia. The team published their findings in the scientific journal Nature.

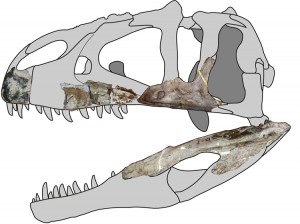

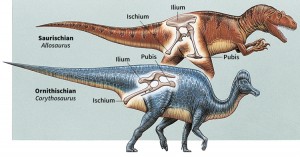

The new dinosaur is an ankylosaur, a member of the group that includes Ankylosaurus and other armored plant-eating dinosaurs. Stegouros was lightly-armored for an ankylosaur, possessing several rows of knobby plates—called scutes—that ran down its back and sides. It was relatively small, only about 6 feet (2 meters) long. It also had thin limbs and an unusually short tail.

The tail of Stegouros has attracted the most attention. Some ankylosaurs possessed tail clubs to defend themselves against predators. But Stegouros had a different tail weapon. Its scutes became larger and sharper down the tail, fusing into a large, bladelike weapon at the tip.

Stegouros’s tail resembles a macuahuitl, a weapon used in the Aztec empire. The macuahuitl was a heavy wooden club lined with several sharp obsidian blades. As with the macuahuitl and the European broadsword, the sheer weight of the swinging tail made it dangerous, more so than the sharpness of the blade. A well-placed swing would have dealt a slicing, shattering blow to the legs of any predator that was trying to catch it.

In paleontology, as in other sciences, one discovery often sheds light on others. The ankylosaur Antarctopelta was discovered in 1986 on James Ross Island, just off the coast of Antarctica. It had unusual vertebrae at the base of its tail, but the rest of the tail was not found. These basal tail vertebrae closely resemble those of Stegouros, so scientists now think Antarctopelta had a similar tail sword.

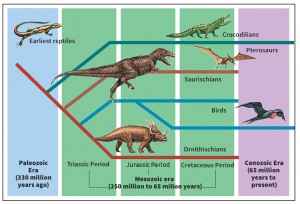

Soto-Acuña and his colleagues suggest that these two strange dinosaurs, along with another named Kunbarrasaurus from Australia, formed a part of a separate group of ankylosaurs. This group diverged from the main ankylosaur lineage early in its history and lived for tens of millions of years in relative isolation near the South Pole.