Maine Statehood 200

Friday, March 13th, 2020March 13, 2020

This Sunday, March 15, is the bicentenary of the northeastern state of Maine. Throughout 2020, bicentennial celebrations and events are commemorating Maine’s entrance to the Union as the 23rd state in 1820.

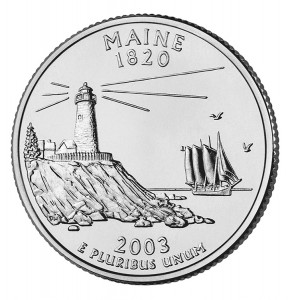

The beautiful, rocky coast of Maine attracts thousands of vacationers to the state each year. The Portland Head Light, in Cape Elizabeth, is one of the best-known American lighthouses. It was built in 1791. credit: © Shutterstock

A special bicentennial flag is flying above Maine’s public and government buildings in 2020. This Sunday, Statehood Day celebrations in Augusta, the capital, include birthday cake, music, poetry, and speeches. Events later in the year include a bicentennial parade, a sailing ships festival, and the sealing of a time capsule. Special bicentennial programs include a “Maine in the Movies” series, which celebrates the state’s role in Hollywood films, and the mass planting of white pine saplings in new or existing public parks. The state is even publishing The Maine Bicentennial Community Cookbook to showcase the state’s unique culinary traditions.

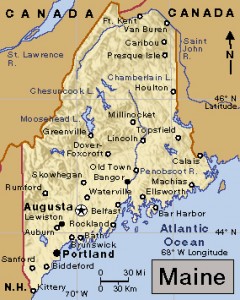

The Maine region was the home of Native Americans for thousands of years before English colonists first settled the area in 1607 (13 years before the Pilgrims landed at Plymouth Rock). Such difficulties as cold weather and a lack of leadership, however, forced the settlers back to England in 1608. Colonists, primarily fishermen, returned to make permanent settlements in Maine in the 1620′s. Maine was a part of Massachusetts throughout its colonial history and for 44 years after the Declaration of Independence established the United States in 1776.

The Maine quarter features a lighthouse on a granite coast and a schooner. The lighthouse is the Pemaquid Point Light, northwest of Portland. The lighthouse dates from the 1820’s and is a popular tourist attraction. Granite is a common feature of Maine’s coastline and one of the state’s leading mined products. The schooner resembles one of Maine’s famous windjammers (sailing ships). credit: U.S. Mint

In 1785, a movement began for the separation of Maine from Massachusetts and for Maine’s admission to the Union as an individual state. Many people in Maine protested heavy taxation, poor roads, the long distance to the capital city of Boston, and other conditions. But before the War of 1812, most voters wanted Maine to remain a part of Massachusetts. The separation movement grew much stronger after the war. Many of those who favored separation won election to the legislature. They swayed many voters to their side. The people voted for separation in 1819, and Maine entered the Union the next year.

The name Maine probably means mainland. Early English fishermen used the term The Main to distinguish the mainland from the offshore islands, where they settled. New Englanders often refer to Maine as Down East. They call people who live in Maine Down Easters or Down Easterners. These terms probably come from the location of Maine east of, or downwind from, Boston. Ships from that port sailed down to Maine, and ships from Maine traveled up to Boston.

The poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow is from Portland, Maine’s largest city, and the American Civil War hero Joshua Chamberlain is from the town of Brewer. The author Stephen King, a native of Portland, sets many of his novels in Maine.