A Most Shocking Electric Eel

Monday, October 28th, 2019October 28, 2019

In September, scientists from the National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., announced the discovery of a new type of electric eel that has the strongest shock of all bioelectric animals: Electrophorus voltai. A native of South America’s Amazon River, E. voltai generates a powerful 860 volts, more than seven times the voltage of a typical American wall socket (120 volts). The eel is named after Alessandro Volta, the Italian physicist who invented the battery.

Electrophorus voltai, seen here, is one of two new electric eel species recently discovered in the Amazon. Credit: © L. Sousa

From 2014 to 2017, the Smithsonian team studied Amazonian electric eels with researchers from Brazil’s University of São Paulo. They tested the eels’ voltages and studied their muscle structures, body shapes, and DNA. To their surprise, the Amazon electric eel—long thought to be a single species, Electrophorus electricus—turned out to be three distinct species. E. electricus remained as the main type, but the team named E. voltai and another electric eel, Electrophorus varii, as new species. The three species differ in voltage as well as in head shape, sense organs, and distribution. E. electricus lives in northern Amazon basin waters, while E. voltai inhabits waters further south. E. varii swims among the slow-flowing lowland Amazon basin waters.

Click to view larger image

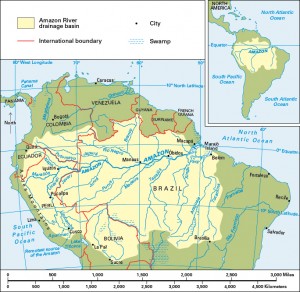

The Amazon River, the world’s second longest river, is 4,000 miles (6,437 kilometers) long. Credit: WORLD BOOK map

The new findings reemphasize the incredible diversity of the Amazon River and rain forest, much of which is still unknown to science, as well as the importance of conservation and saving the region from deforestation, logging, and fires.

The electric eel stuns its enemies and prey with a powerful electric shock. The electricity-producing organs take up most of the body. The other inner organs lie just behind the head. Credit: © Andre Seale, Alamy Images

Electric eels are a long, narrow fish that produce strong electric discharges, or shocks. The animals are not true eels, but rather a type of knifefish. An electric eel discharge can kill a fish and stun such potential predators as caimans (large reptiles) or humans. However, electric eels rarely harm people in the wild.