1968 Democratic Convention

Tuesday, August 28th, 2018August 28, 2018

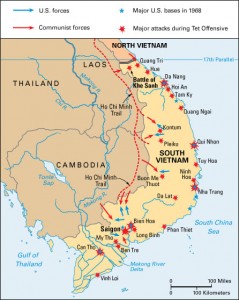

Fifty years ago this week, from Aug. 26 to 29, 1968, political leaders gathered for the Democratic National Convention in Chicago to nominate that party’s candidate for president of the United States. The convention is normally a festive, hopeful, and inspiring event, but few things were “normal” in the United States of 1968. The ongoing Vietnam War was a point of bitter contention among the American public. The assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy had produced shock, grief, and anger in the country. Racial tensions were high, and social and political divides had never been sharper. Political protests turned violent during the convention, and America watched on television as police battled the people in the streets of Chicago.

Protesters confront National Guard troops on Chicago’s Michigan Avenue during the Democratic National Convention on Aug. 26, 1968. Credit: Library of Congress

Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley, second only in power in the Democratic party to President Lyndon B. Johnson, was prepared for unrest. The city’s police were out in force for the convention, the National Guard had been mobilized, and steel barrier walls topped with barbed wire were ready to slide into place. A heatwave and taxi driver strike added to the kindling of political discord, and as protesters took advantage of the convention’s media spotlight to plead their cases, the ingredients were ready for confrontation.

Richard J. Daley, the mayor of Chicago from 1955 to 1976, was one of the most powerful Democratic politicians in the United States. Credit: AP Photo

People from across the country came to Chicago to participate in protests during the convention. People stridently called for racial equality, radical political change, an end to the war in Vietnam, and other causes. Protests took place around the city, and roaring chants and catcalls greeted political delegates as they emerged from cars to enter the International Amphitheatre on Chicago’s south side (the indoor arena was torn down in 1999). Inside the convention, there was yelling too. Delegates strongly disagreed on who should replace President Johnson—who had chosen not to run for a second full term—on the Democratic presidential ticket. The death of Robert Kennedy had opened a void in Democratic leadership, and the contenders to fill that void vastly differed on the country’s issues.

Democratic presidential candidate Hubert H. Humphrey addresses the crowd at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago on Aug. 29, 1968. Credit: AP Photo

Many Chicago police officers, on edge and pushed to the limit of their tolerance, began beating protesters who would not respond to orders to withdraw, move aside, or quiet down. Protesters responded by hurling rocks and other projectiles at the police, and the commotion turned to riot. Police sprayed people with mace and fired tear gas into the crowds. Hundreds of people were arrested, often with great physical violence, and many protesters and police were injured. Many innocent bystanders were also hurt, including members of the media trying to cover the unrest.

Television news broadcast the mayhem around the country, and people connected the violence with the Democratic Party. The eventual Democratic presidential nominee, Johnson’s Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey, did not please many Democratic voters. Humphrey lost to the Republican “law and order” candidate Richard M. Nixon in the election. Nixon lost favor with Americans, however. The president promised to end U.S. involvement in Vietnam, but he increased air raids and sent American troops into battle for five more years. In 1974, after his Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned while under criminal investigation, Nixon too resigned to prevent being impeached because of the Watergate scandal.