Is There Life on Venus?

Friday, December 8th, 2023

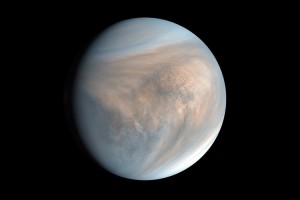

An image of Venus, made with data recorded by Japan’s Akatsuki spacecraft in 2016, shows swirling clouds in the planet’s atmosphere.

Credit: PLANET-C Project Team/JAXA

Could there be microscopic life in the clouds of the planet Venus? The idea may seem far-fetched, but in 2020, scientists discovered a tantalizing hint that it could be true, in the form of a strange gas in Venus’s atmosphere. They are still studying to see what the planet might be hiding!

Venus has been called Earth’s twin. It’s next door to Earth, about the same size as Earth, and covered by an atmosphere of thick, swirling clouds. All of these features made it a tempting target during the early exploration of space. Speculators even imagined dense jungles covering the planet’s surface. When the first landers visited Venus in the 1970’s, however, they revealed a searing environment of 870 °F (465 °C) with pressures 90 times greater than that at Earth’s surface. Clouds of sulfuric acid filled the sky. The search for other life within the solar system quickly shifted to the more temperate Mars.

The new evidence was discovered by an international team of scientists that was actually more interested in exoplanets, planets orbiting distant stars. The team was led by Jane Greaves at Cardiff University in the United Kingdom. Scientists are constantly looking for ways to study exoplanets for signs of alien life. One way is to study the spectra (ranges of light) reflected by exoplanets for clues to chemicals in their atmosphere. One such chemical may be the gas phosphine. On Earth, phosphine is produced by microbes in anaerobic environments—places without oxygen. The gas is short-lived, so to be present in a planet’s atmosphere, it must be replenished continually. So, the presence of phosphine in an exoplanet’s atmosphere could be a sign of ongoing alien life.

The team recorded atmospheric data from Venus in an attempt to establish a benchmark for the spectral signature of an Earth-sized planet without phosphine. To their surprise, their findings indicated that the Venusian atmosphere did contain phosphine. After asking another team of scientists to double-check their results and studying the planet with a more powerful telescope, the evidence of phosphine was confirmed. Scientists do not yet know of a nonbiological way for phosphine to arise on Venus, pointing to the amazing possibility that Venus may harbor microscopic life. If such life exists, it is likely to be found in Venus’s clouds, where conditions are less hellish than those on the surface.

Greaves and her team emphasized that scientists are a long way from determining that there is life on Venus. The authors noted, for example, that sulfur dioxide produces a similar spectral signature to phosphine under certain conditions, raising the possibility that other molecules may mimic phosphine.