JWST Sets Its Sights on TRAPPIST-1

Thursday, December 29th, 2022

This artist’s illustration imagines the view from the surface of one of the planets in the TRAPPIST-1 planetary system. Astronomers think that some of the planets in this system may have a substantial ocean of water, a necessary ingredient for life.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

One of the most stunning astronomical discoveries of the last decade was an entire system of exoplanets, relatively close to Earth, that have the potential to host life. During a Dec. 13, 2022 conference, astronomers reported preliminary findings about the system gathered by the powerful new James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

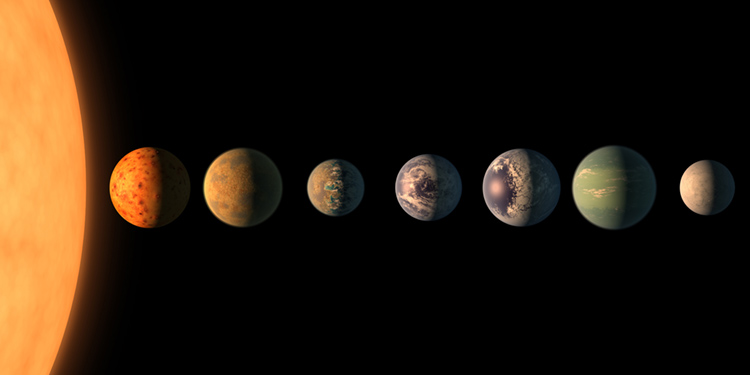

This artist’s illustration shows what the TRAPPIST-1 planetary system may look like. The planetary system has seven planets that rapidly orbit close to the parent star. Three of the planets orbit within the habitable zone of the star where liquid water can exist on a planet’s surface.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

TRAPPIST-1 is a red dwarf star about 40 light-years from Earth in the constellation Aquarius. One light-year equals the distance light travels in a vacuum in a year, about 5.88 trillion miles (9.46 trillion kilometers). TRAPPIST-1 is notable for having seven orbiting planets. Astronomers classify the planets as terrestrial, meaning they have Earthlike qualities. All of them orbit the star within or near a region that astronomers call the habitable zone. That is, in that region in which liquid water can exist on a planet’s surface. Scientists consider liquid water to be an essential ingredient for life.

The first three planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system were discovered in 2015. These were discovered by astronomers using the Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope (TRAPPIST) robotic telescope pair, located at La Silla Observatory in Chile and Oukaïmeden Observatory in Morocco. Scientists using the Spitzer Space Telescope and the Very Large Telescope in Chile announced in 2017 that they had confirmed the discovery of those three planets and had discovered four more planets.

The potential of these planets to host conditions favorable for life made the TRAPPIST-1 system a major target for the JWST. This advanced satellite observatory was launched in December of 2021 and began conducting scientific observations in mid-2022. Earlier that year, JWST characterized the atmosphere of the giant exoplanet WASP-96b as a proof-of-concept, setting the stage for TRAPPIST-1 observations.

The preliminary results from two of the TRAPPIST-1 planets confirm that they do not have hydrogen atmospheres. They may have no atmospheres, or they may have atmospheres composed of other gases, including carbon dioxide, methane, and water vapor. Such atmospheres could make these planets hospitable for life.

Because these exoplanets are so small, even the powerful JWST needs to view the system for extended periods to gather accurate data. But the system’s diminutive proportions will speed up the observation process. JWST detects minute changes to the star’s light as each planet passes in front of it. The seven planets whirl around TRAPPIST-1 with orbital periods of 1.5 to 18.8 Earth days. In contrast, Earth’s orbital period (also called a year) is about 365 days, and Mercury’s is 88 Earth days. (Because TRAPPIST-1 is a small, cool star, these tight orbits still lie within or near its habitable zone.) Astronomers are confident that they will have a good “family portrait” of the TRAPPIST-1 within a year.

JWST has already racked up impressive observations after just a half-year of activity. With its study of TRAPPIST-1, it will help bring astronomers closer to answering one of the most fundamental questions in science: are we living things on Earth alone in the universe, or not?