The Universe Liked Saturn and Put a Ring On It

Wednesday, March 30th, 2016March 30, 2016

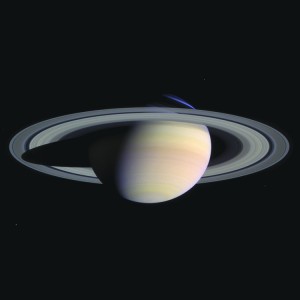

Natural color image of Saturn and its rings taken by Cassini’s narrow angle camera on March 27, 2004. Credit: NASA/JPL/Space Science Institute

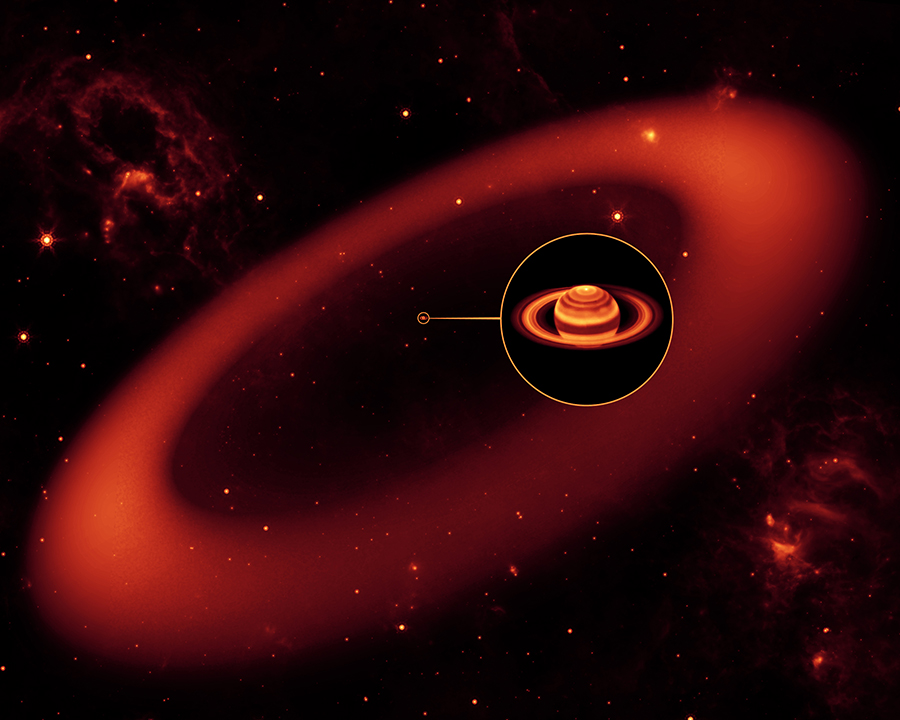

Imagine what Saturn would be like without its rings. Though large, it would be quite unremarkable as a planet compared to Jupiter, given that planet’s even greater size, colorful cloud bands, and swirling storms. Aside from its large moon Titan, there would be little about Saturn to excite astronomers and the general public. This ringless state may have been Saturn’s plight in the relatively recent past, according to a new report. Matija Cuk from the Search for Extra-terrestrial Intelligence (SETI) Institute and Luke Dones and David Nesvorny from the Southwest Research Institute of San Antonio, Texas, published findings in The Astrophysical Journal that Saturn’s rings and some of its moons are only about 100 million years old.

Saturn’s rings consist of ice particles that travel around the planet. It has seven main rings, which vary greatly in width. The outermost ring, called the E ring, may measure more than 180,000 miles (300,000 kilometers) across. All of the the rings also vary greatly in thickness. Most are probably under 100 feet (30 meters) thick. They are, however, all so thin that they cannot be seen with Earth-based telescopes when their edge is in direct line with Earth.

Like Saturn itself and the rest of the planets in the solar system, scientists had assumed that Saturn’s rings and satellites (moons) formed about 4.6 billion years ago and had been around ever since. In 2012, however, a team of French scientists suggested that tidal forces (forces created by the uneven pull of gravity on large objects) should have pushed Saturn’s rings and inner moons further from the planet. Thus, the researchers thought the rings might not be as old as the rest of the Saturn system.

Cuk, Dones, and Nesvorny helped support this idea. Occasionally, moons of large planets drift into orbital resonances, when the amount of time each one takes to orbit the planet forms a simple fraction. (For example, if one moon orbits a planet two times for every three orbits another moon makes, those moons are in orbital resonance.) When this happens, the interaction of gravity between the moons—even if they are small—can fling them into longer, more eccentric, orbits. The three scientists found that the orbits of three satellites of Saturn—Dione, Rhea, and Tethys—had not been changed much due to the effects of orbital resonances. They suggested the moons were formed—along with Saturn’s rings—close to where they orbit today about 100 million years ago.

While 100 million years seems like quite a long time indeed, it is the blink of an eye in astronomical terms. Most of the solar system hasn’t changed much in 4 billion years. The scientists speculate that around 100 million years ago, changes in the orbits of two or more earlier moons caused them to collide. Dione, Rhea, and Tethys would have formed from portions of this debris. Some of the debris would have also rained down on the rest of the Saturn system, peppering older moons with fresh craters. The rest of the debris remained locked in orbit around Saturn as the gorgeous rings we see today. More research must be done to confirm the findings, but it appears that Saturn’s most distinctive feature may be its most recent one.