Greetings from Interstellar Space

Monday, November 25th, 2019November 25, 2019

This month, scientists at the United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) released their latest findings from decoded transmissions sent from the space probe Voyager 2 in interstellar space (the space between the stars). About a year ago, Voyager 2 became the second spacecraft (following its twin, Voyager 1) to enter interstellar space, exiting the heliosphere, a vast, teardrop-shaped region of space containing electrically charged particles given off by the sun.

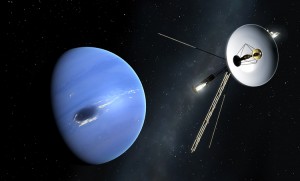

Voyager 2, seen here passing Neptune in 1989, entered interstellar space in late 2018. Credit: © Mark Garlick, Science Source

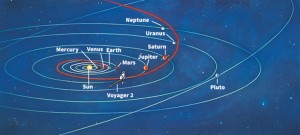

The sun and all the planets are inside the heliosphere. Scientists estimate that the nose (blunt end) of the heliosphere is about 9 billion to 15 billion miles (15 billion to 24 billion kilometers) from the sun. Voyager 1, launched in September 1977, crossed the boundary from heliosphere to interstellar space in 2012. The crossing was marked by a steady drop in temperature and an increase in the density of charged particles known as plasma. Voyager 1 also detected an abundance of cosmic rays (particles accelerated by exploding stars) in interstellar space and provided evidence that the heliosphere protects Earth and the other planets from much interstellar space radiation.

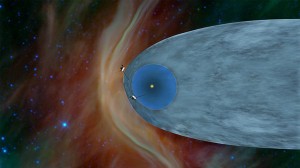

This artist’s depiction shows the approximate locations of the two Voyager spacecraft relative to the sun, the bright spot in the center, in the mid-2010′s. In 2012, Voyager 1, shown as the upper probe in the image, sailed beyond the heliopause and into interstellar space. Voyager 2, the lower probe in the image, crossed the heliopause in 2018. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Voyager 2 was launched a month before Voyager 1 in August 1977. Slightly slower than its twin craft and following a different course, Voyager 2 reached the heliopause (the edge of the heliosphere) in November 2018. Voyager 2 also detected changes in temperature and plasma and cosmic ray density, but the heliosphere at Voyager 2′s crossing point appeared to be sharper and thinner. This could be explained by Voyager 2 crossing the heliopause at a different location or at a less angled trajectory or by crossing during a period of lower solar activity than that experienced by Voyager 1 in 2012. The sun goes through a roughly 11-year cycle of high and low activity, theoretically causing the heliosphere to expand and contract or thicken and thin. Both spacecraft found that particles from the sun are trickling through the somewhat porous heliopause into interstellar space. Voyager 2 also confirmed Voyager 1′s detection of similar magnetic fields on both sides of the distant boundary.

This artist’s impression shows Voyager 1 passing through the heliopause in 2012. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Both Voyager space craft are powered by slowly decaying plutonium. In 1977, scientists did not know exactly how long the space probes would continue to operate, nor did they know if, when, or where they would reach interstellar space. Now that the probes are there, scientists hope to learn more about the distant realm before the Voyagers power down sometime in the next few years. Voyager 1 is currently more than 13.6 billion miles (22 billion kilometers) from the sun, and Voyager 2 is about 11.3 billion miles (18.2 billion kilometers) away. After they lose power, scientists expect both to continue sailing through space for billions of years.