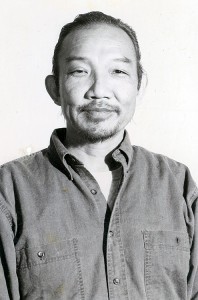

LGBTQ+ Pride Month: Kiyoshi Kuromiya

June is LGBTQ+ Pride Month. All month long, Behind the Headlines will feature lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer or questioning pioneers in a variety of areas.

Kiyoshi Kuromiya was an influential American civil rights activist and writer. He helped organize and took part in anti-war demonstrations and protests for civil rights and gay rights. Later, Kuromiya became an advocate for people with AIDS and worked to connect patients with the latest research.

Steven Kiyoshi Kuromiya was born May 9, 1943, at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center near Cody, Wyoming. He and his family were among the 110,000 Japanese Americans forcibly relocated by the United States government during World War II (1939-1945) as part of a policy called internment. One of his uncles, also a Heart Mountain resident, refused to participate in the draft and served three years in prison. After the war ended, Kuromiya’s family moved to Ohio and then to California. During this time, Kuromiya began to realize that he was gay. He used special library privileges his parents had gotten him to read about being gay at the county library. As a teen, he subscribed to the few gay news publications available at the time.

In 1961, Kuromiya moved to Philadelphia to attend the University of Pennsylvania, where he studied architecture. There, he became involved in the civil rights movement. He participated in diner sit-ins in Maryland and protests against nuclear testing. In 1963, he attended the March on Washington and afterward met the American civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. In 1965, he joined a group of protesters staging a sit-in at Independence Hall in Philadelphia and participated in the famous march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. During the march, he was knocked unconscious by the police and required stitches. He became close to the King family during these protests, and he helped to care for the King children in the immediate aftermath of their father’s assassination.

In 1968, Kuromiya organized a protest against the Vietnam War (1957-1975). To draw a crowd, he started a rumor that a dog was going to be set on fire. When a crowd of people arrived to try and stop it from happening, they instead found a flier from Kuromiya. It read, “Congratulations on your anti-napalm protest. You saved the life of a dog. Now, how about saving the lives of tens of thousands of people in Vietnam?” Kuromiya was also arrested that year for distributing a poster that encouraged people to burn their draft cards, a criminal act.

Kuromiya joined one of the first protests for gay rights in 1965, despite not being fully out at the time. The Annual Reminder picket lines at Independence Hall were organized by the East Coast Homophile Organizations (ECHO), a collaboration between several early gay rights groups, and held on July 4 every year. Kuromiya later became one of the founders of the Philadelphia branch of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), a more radical group fighting for gay rights. The loosely structured group lasted only about a year. Kuromiya continued to host a Gay Coffee Hour on the University of Pennsylvania campus, which became the first gay organization to receive funds from the university.

During the 1970’s and 1980’s, Kuromiya worked closely with the American engineer and inventor Buckminster Fuller. They co-authored Critical Path, published in 1981. The book explored how architecture, design, and technology can be used to solve world problems.

Kuromiya was diagnosed with AIDS in the late 1980’s. Afterward, he became heavily involved in advocacy organizations such as AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power (ACT UP) and People With AIDS (PWA). He founded the Critical Path Project, a group that published newsletters with information on AIDS research. Additionally, he established a hotline for people with AIDS to get more information about treatments. He set up a computer lab in his home to enable people with AIDS to connect via the internet, which was a relatively new technology at the time.

In 1996, Kuromiya was one of the plaintiffs in a successful case to get the Communications Decency Act thrown out. This law had placed restrictions on what information could be shared publicly, prohibiting “patently offensive” materials. The law had threatened efforts by the Critical Path Project to get AIDS-related information to people who needed it. Kuromiya lost a 1999 class-action suit that sought to overturn bans on the use of marijuana for medicinal and therapeutic purposes in the United States.

Kuromiya died on May 10, 2000. He has been honored with a spot on the San Francisco Rainbow Walk and a placard on the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor at the Stonewall Inn, now a national monument.