The Black Hole Event

April 12, 2019

On Wednesday, April 10, scientists with the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) team published a photograph of the invisible—or at least the area around the invisible. The EHT captured an image of an event horizon (the surface of a black hole) for the first time. The EHT is a global collection of radio telescopes that work together as one giant telescope. As its name implies, the EHT was created to observe an event horizon, a mission that has at last been accomplished. The EHT began its quest in 2006, and has since greatly expanded its network.

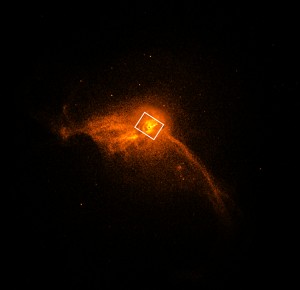

On April 10, 2019, scientists with the Event Horizon Telescope team released this first ever image of a black hole—or at least the event horizon surrounding a black hole. Credit: EHT Collaboration/ESO

A black hole is a region of space whose gravitational force is so strong that nothing can escape from it, not even light. The event horizon is the “point of no return” for a black hole: Anything that crosses this horizon is sucked into the black hole forever. Because light cannot escape a black hole, all black holes are invisible and cannot be directly photographed. But physicists predicted that an image of the area surrounding a black hole would reveal a halo of high-energy matter and radiation around a circular shadow.

The boxed area in this image shows the black hole at the core of the M87 galaxy.

Credit: NASA/CXC/Villanova University/J. Neilsen

Heino Falcke, a German astrophysicist now at Radboud University in the Netherlands, discovered that this halo would emit radio waves detectable on Earth. He helped found the EHT to photograph event horizons through these radio waves. The collection of ground-based radio telescopes participating in the EHT project stretches from Hawaii to Europe and all the way south to Antarctica. Several dozen of the world’s leading observatories and universities contribute to the project.

The EHT observed a supermassive black hole at the center of a huge galaxy called Messier 87, or M87, some 55 million lightyears from Earth. A supermassive black hole is a type of black hole with a mass from 1 million to billions of times the mass of our solar system’s sun. Many galaxies have a supermassive black hole near their centers. The supermassive black hole at the center of M87 is one of the largest ever discovered, some 6.5 billion times the mass of our sun. The diameter of its event horizon is roughly the size of our entire solar system.

It took an enormous effort to produce the image released this April. Two years ago, in April 2017, eight radio telescopes of the EHT simultaneously observed the M87 black hole for 10 days. The observations had to be precisely synchronized (scheduled) by atomic clock to combine and match up their images. In total, the observatories collected more than 5 petabytes of data, equal to the text of 88 million print editions of the World Book Encyclopedia. (A petabyte is 1,000 terabytes. A terabyte is a measure of computer information or memory equal to about 1 trillion bytes). This was so much information that it was faster to fly the data by airplane between the laboratories that analyzed the data than to transfer it over the internet. An American computer scientist named Katie Bouman developed a special algorithm to combine the data from the eight telescopes into a single image.

Just like the detection of gravitational waves three years ago, this work promises to revolutionize astronomy. Each year, new observatories join the EHT, strengthening its resolution (image sharpness). The EHT has observed black holes other than the one at the core of M87, including the one at the center of our own Milky Way galaxy, Sagittarius A*. EHT scientists think they will be able to produce an image of that event horizon soon. Scientists might also be able to sharpen the image of the M87 black hole in the coming months.