Veterans Day: Remembering the Code Talkers

Friday, November 10th, 2023

Code talkers were Indigenous Americans who used their languages to help the United States military communicate in secret. This black-and-white photograph shows two Navajo code talkers operating a radio during World War II (1939-1945). The Navajo language was unknown to the Germans and Japanese and proved impossible for them to decipher.

Credit: NARA

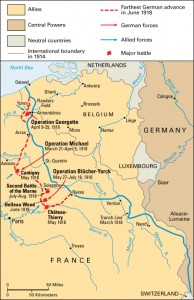

On November 11, the anniversary of the end of World War I (1914-1918), the United States observes Veterans Day honoring men and women who have served in the United States armed services. In 1919, President Woodrow Wilson proclaimed November 11 as Armistice Day to remember the tragedies of war and appreciate peace achieved by the armistice (truce). In 1938, Armistice Day was made a federal holiday. Congress renamed the day Veterans Day to honor all United States Veterans in 1954. Around the world, the anniversary of the end of World War I is a day to remember those who have died in war. Australia, Canada, and New Zealand observe Remembrance Day on November 11. The United Kingdom observes Remembrance Day on the Sunday closest to November 11.

November is also Native American Heritage Month, a time to observe the cultures, histories, and traditions of Indigenous Americans. Many Indigenous Americans have served in the United States armed forces, contributing to the United States’ success in World War I (1914-1918) and World War II (1939-1945). Most notably, Indigenous Americans called the Code Talkers developed and used codes that enabled the United States and its allies to communicate globally without enemy interference.

The Code Talkers were small groups of Indigenous Americans who served in the United States armed forces in World War I and World War II. Code Talkers developed and used codes in Indigenous American languages to send secret messages, helping the United States and its allies win both wars.

The engineer Philip Johnston suggested the United States Marine Corps use Navajo language as a code during World War II. He grew up on a Navajo reservation and knew that the Navajo language is unwritten, difficult to decipher (decode), and unknown to most people who are not Navajo. In 1942, the United States Marine Corps recruited 29 Navajo men to develop the code. The code talkers used familiar wards to represent U.S. military terms. For example, bombs were called eggs in Navajo. They also created a new phonetic alphabet with Navajo words.

Similarly, in World War I, 19 Choctaw men had served in the U.S. Army, sending and receiving messages based on the Choctaw language. During World War II, 17 Comanche men used their language for code in the U.S. Army Signal Corps.

![First organizational meeting of the American Legion in Paris, France. Caucus was held March 15,16,17 1919 and convened by members of the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). Writing in pencil on back of the photo reads, "Spring 1919 Cirque de Paris First [illegible] Legion Convention 3-day organization meeting." Credit: Harry S. Truman Library & Museum](https://bth.worldbook.com/bth/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/pc381715-300x188.jpg)