Mythic Monday: Fiery Phoenix

Monday, October 9th, 2017October 9, 2017

A fire rises… But the streaks of red and gold are not flames, they are feathers, and the blaze is a great bird taking flight. The fiery phoenix, the fabled bird of Greek mythology, appeared in many stories and inspired the name of Arizona’s capital and largest city. The mythological phoenix was a fascinating creature with some peculiar traits: Every phoenix was male; there was never more than one phoenix at a time; each phoenix lived exactly 500 years; and, most famously, at the end of its life cycle, the phoenix burned itself on a funeral pyre. Another phoenix then rose from the ashes with renewed youth and beauty.

This etching of the fiery phoenix appeared in Friedrich Justin Bertuch’s Kinderbuch (children’s book) of mythological creatures in 1806. Credit: Friedrich Justin Bertuch

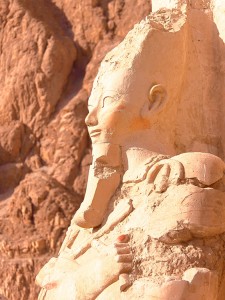

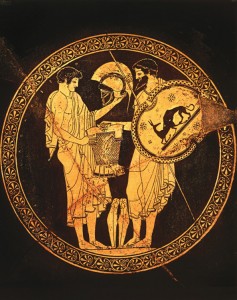

According to legend, each young phoenix would carry the remains of its predecessor to the altar of the sun god Helios in the Egyptian city of Heliopolis (City of the Sun). The bird’s rebirth and rising branded it a symbol of immortality, resembling the setting and rising of the sun each day. Phoenix feathers were brilliant reds, purples, and yellows, and the eagle-sized bird subsisted solely on dewdrops, if anything. Its song was so captivating that even Helios would stop his chariot to listen. The ancient Greeks likely based the phoenix on the stork-like Egyptian bennu, a sacred bird that represented the Egyptian sun god, Re.

The mythologies of other cultures also have versions of the fiery mythological bird. The Fèng Huáng is similar to the phoenix in China, where it is a sacred symbol of the royal empress. Also given dragon properties, the Fèng Huáng represents loyalty, justice, goodness, and honesty. The Native American thunderbird is a giant animal with massive wings that defends people from evil with supernatural power and strength. The thunderbird manipulates thunder, lightning, and rain. Slavic myth tells of the Russian firebird, a falcon protector blessed with strength and courage.

In literature, the phoenix is an extraordinary character named Fawkes in the Harry Potter series by J.K. Rowling. Fawkes is a great red and gold songbird reborn from ashes. His tears have healing powers, he is strong enough to carry several people in flight, and he can teleport. Phoenix tail feathers are used as powerful cores of wizards’ wands. Fawkes is loyal to his companion, Dumbledore, and is a brave and fierce defender.