The Big Easy, 10 Years On

Friday, August 28th, 2015August 28, 2015

A street intersection lies flooded near downtown New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina struck the city in August 2005. Ten years later, some aspects of the city have yet to recover. (© Chris Graythen, Getty Images)

Residents of New Orleans and other areas along the U.S. coast of the Gulf of Mexico made plans to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the landfall of Hurricane Katrina on Saturday, August 29. Legions of news reporters have descended upon the Crescent City (a nickname for New Orleans, as is Big Easy). Once there, reporters file anniversary reports, drawing comparisons between the pre- and post-storm city. They have found miles of new and reinforced levees and clear signs of rebirth and stagnation, joy and despair.

President Barack Obama spoke on Thursday, August 27, in New Orleans, where he met with Mayor Mitch Landrieu and a number of residents from the city, who had revived their lives and neighborhoods after the storm. Speaking at the Andrew P. Sanchez Community Center in the Lower Ninth Ward, the president recalled the pain and loss in a city where four-fifths of the land was once covered by floodwater. He praised the wherewithal of Gulf Coast residents and the progress they have made with more than $100 billion in federal government spending, much of which has gone to tear down and rebuild homes and public facilities, re-engineer and construct vast lengths of flood barriers, and restore wetlands that cushion the region from future storm surges (huge waves of water driven inland by wind).

“As hard as rebuilding levees is, as hard as rebuilding housing is, real change—real lasting structural change—that’s even harder,” Obama said, acknowledging progress and addressing continuing challenges. “And it takes courage to experiment with new ideas and change the old ways of doing things. That’s hard. Getting it right and making sure that everybody is included and everybody has a fair shot at success—that takes time.”

On August 29, 2005, Katrina’s wind gusts reached up to 125 miles (200 kilometers) per hour as the storm smacked several Gulf Coast communities. Katrina pushed a storm surge that reached up to 34 feet (10.4 meters) high. The surge reached hundreds of feet inland. In New Orleans, the storm surge moved rapidly up man-made channels, breaching levees and flooding low-lying neighborhoods. One thousand eight hundred people died, most of them in New Orleans. Hundreds of thousands were left homeless, and tens of thousands fled their hometown. Many of them would never return.

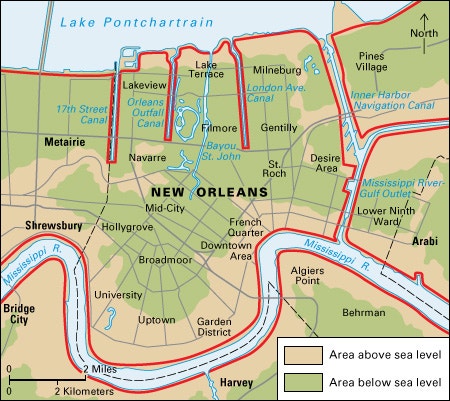

Much of New Orleans lies below sea level and is protected by a system of flood barriers called levees. The red lines on this map show the city’s major levees. Areas below sea level suffered the greatest damage from Hurricane Katrina in 2005. (World Book map)

Ten years on, evaluation of the region’s progress falls largely along class and income lines, with poor blacks in the city and poor whites from the bordering parishes most likely to say that the area’s much reported-upon recovery has been overblown. Wealthier citizens, many of whom lived in the French Quarter and other neighborhoods on higher ground, suffered less and tend to have a sunnier picture of the region’s recovery.

In such neighborhoods as the Lower Ninth Ward, residents take note of freshly painted, rehabbed homes with tidy lawns and gardens competing with adjacent overgrown lots and empty houses, which shelter breeding snakes and rats, drug dealing, and other illicit activities. In St. Bernard Parish, southeast of the city, just about every home—some 25,000 structures—was damaged or destroyed by either the storm surge or by steeping for weeks in stinking oil-polluted floodwater. Today, roughly two-thirds of the homes in the parish have been rebuilt, with a population that has rebounded to about two-thirds of its pre-storm total. Most of the parish’s homes lie within the region’s bolstered levee system, though some areas remain unprotected and are at severe risk of flooding from future storms and rising sea levels caused by global warming.

As much as some boosters would paint the city as being back to normal, the face of New Orleans has changed. Most of its public schools were shut down and later reopened as charter schools operated under a private-public partnership. And as neighborhoods rebound, gentrifying outsiders have altered the character of the place. (Gentrification is a process whereby wealthier people move into poor urban neighborhoods, changing the balance of the neighborhood.) Prior to Katrina’s landfall, more than two-thirds of the city claimed African American heritage. Tens of thousands of blacks fled the city during pre- and post-storm evacuations, however, and many settled permanently in other locales. Today, the city remains majority black, though whites and Hispanics represent increasing shares of the city’s ethnic mix. Tremé (treh MAY), one of the city’s oldest traditionally African American neighborhoods, now has twice as many white residents as in 2005.

The physical and demographic changes brought on by Katrina have been jarring to those who have long called New Orleans home. Nothing—not even billions in federal spending—can begin to replace the lost lives or the interesting character of the city before the storm. But New Orleans, as much as anywhere in America, is accustomed to change. Flags of France, Spain, the Confederate States, and the United States have flown over the South’s oldest major city, and its resilient residents are unlikely ever to raise a white banner above their beloved and troubled home.

Other World Book articles