Our Earliest Ancestor

Monday, September 30th, 2019September 30, 2019

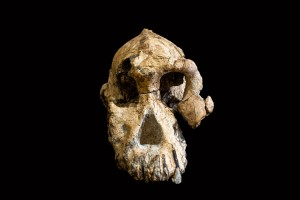

Last month, in late August, scientists published a description of a 3.8-million-year-old fossil skull, allowing people to gaze into the face of perhaps our earliest ancestor, Australopithecus anamensis. According to one researcher, the remarkable fossil is the most complete skull of the “oldest-known species” of the human evolutionary tree. The important fossil helps define the ancient human evolutionary family, but it also brings more questions to the often cloudy relationships among that family’s members.

Paleontologists discovered the near-complete skull of Australopithecus anamensis in Ethiopia in 2016. Credit: © Dale Omori, Cleveland Museum of Natural History

A. anamensis belongs to the hominin group of living things that includes human beings and early humanlike ancestors. A team of paleontologists led by Yohannes Haile-Selassie from the Cleveland Museum of Natural History found the hominin skull in 2016 at a site called Woranso-Mille in the Afar region of Ethiopia. The fossil, officially known as MRD-VP-1/1 (MRD for short), was discovered in two halves that fit together, making up a nearly complete skull. The skull’s position in volcanic sediments enabled scientists to determine its age—3.8 million years—with great precision. The anatomical features of the skull helped identify it as A. anamensis, one of the earliest known hominin species. This species was first identified from a handful of fossil skull fragments and other bones discovered at Lake Turkana in northern Kenya in the 1990’s. Those specimens are between 4.2 million and 3.9 million years old.

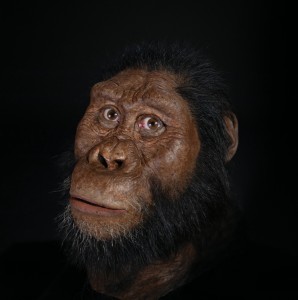

Scientists used the fossilized Australopithecus anamensis skull to create this image of one of humankind’s earliest ancestors. Credit: © John Gurche/Matt Crow, Cleveland Museum of Natural History

The MRD skull shows that A. anamensis had a small brain, a bit smaller than that of a modern chimpanzee. The skull more closely resembles an ape than a modern human, with a large jaw and prominent cheekbones, but the canine teeth are much smaller and more humanlike. And, like humans, A. anamensis walked upright on two legs. Sediments and other fossils show that the region where the skull was found was arid, but the ancient creature died in a vegetated area near a small stream that entered a lake.

The site in Ethiopia where MRD was discovered is not far from the village of Hadar, where fossils of another early hominin, Australopithecus afarensis, were first discovered in 1974. A. afarensis is known mainly from the partial skeleton of an adult female, the famous “Lucy,” found in deposits dating to about 3.2 million years ago. Other A. afarensis fossils date to nearly 3.8 million years ago, which suggests Lucy and her kind may have coexisted with A. anamensis.

Most scientists, however, think that Lucy and her kind evolved from A. anamensis, and that the transition occurred as one species disappeared and the other took over. Scientists now understand that A. anamensis could still be ancestral to Lucy, but that other A. anamensis populations continued to thrive unchanged as her neighbors. The prehistoric landscape of East Africa had many hills, steep valleys, volcanoes, lava flows, and rifts that could easily have isolated populations over many generations. Over time, the populations eventually diverged. Scientists think that one of these species eventually gave rise to Homo, the human genus.