African American History: Tuskegee Airmen

Wednesday, February 19th, 2020February 19, 2020

In honor of Black History Month, today World Book remembers the Tuskegee Airmen, a group of African Americans who served in the United States Army Air Corps during World War II (1939-1945). The name Tuskegee Airmen is used most often to refer to combat pilots, but the group also included bombardiers, navigators, maintenance crews, and support staff. Members of the Tuskegee Airmen were the first African Americans to qualify as military aviators in any branch of the armed forces. Many became decorated war heroes. In 2007, the United States awarded the Tuskegee Airmen the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest civilian award given by Congress.

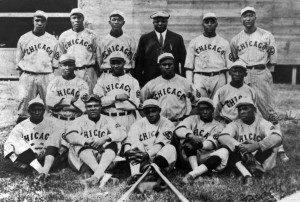

The Tuskegee Airmen were a group of African American pilots, crew, and support staff that served in the Army Air Corps during World War II (1939-1945). This photograph, taken in Ramitelli, Italy, in 1945, shows airmen at a tactical meeting. Credit: Library of Congress

Last February, the National Air and Space Museum at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., hosted an event called “African American Pioneers in Aviation and Space.” Among the special guests at the event was the Tuskegee Airman Charles McGee, who turned 100 years old in December 2019. McGee flew 409 aerial combat missions during World War II, the Korean War (1950-1953), and the Vietnam War (1957-1975). His military honors include the Legion of Merit, the Distinguished Flying Cross, and two Presidential Unit Citations. McGee was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 2011.

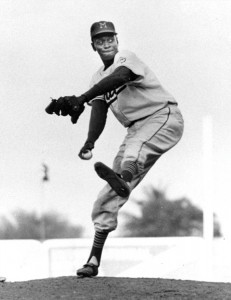

Daniel “Chappie” James, one of the famous Tuskegee Airmen, poses with his P-51 Mustang fighter plane during the Korean War. Credit: U.S. Air Force

At the time of World War II, the U.S. War Department had a policy of racial segregation. Black soldiers were trained separately from white soldiers and served in separate units. They were not allowed into elite military units. In 1941, under pressure from African American organizations and Congress, the Army Air Corps began accepting black men and admitting them into flight training. The men were trained at Tuskegee Army Air Base, near Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University), a college for black students in rural Alabama.

The training program began in 1941. One of the first men to earn the wings of an Army Air Corps pilot was Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., who later became the first black general in the U.S. Air Force. Davis commanded the 99th Pursuit Squadron, the nation’s first all-black squadron, which trained at Tuskegee. The 99th operated in northern Africa. Davis later commanded the 332nd Fighter Group, which also trained at Tuskegee. The 332nd became known for its success escorting bombers on missions over Europe.

Training at Tuskegee ended in 1946. A total of 992 pilots graduated from the program. The success of the Tuskegee aviators helped lead to a decision by the U.S. government calling for an end to racial discrimination in the military. Well-known graduates of the Tuskegee program include Daniel James, Jr., who was the first black four-star general; and Coleman A. Young, who served as mayor of Detroit from 1973 to 1993.