Hong Kong’s Summer of Protest

September 25, 2019

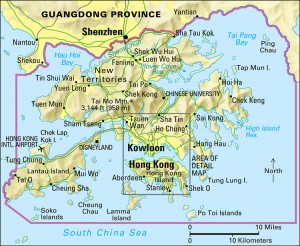

Since June 2019, massive protests have taken place in Hong Kong, a special administrative unit of China. The city and region of Hong Kong—located on a peninsula and group of islands—enjoy a high degree of autonomy (self-rule). Hong Kong maintains a free-enterprise economy within China’s Communist economic system. The “one country, two systems” relationship is not always a happy one, however, and the people of Hong Kong often resent being subjected to mainland China’s different rules.

Protesters face off with police in Hong Kong on June 12, 2019. Credit: © Dale De La Rey, Getty Images

In June 2019, the largest protests in Hong Kong’s history were triggered by a proposed bill that would have allowed people Hong Kong accused of crimes in to be extradited (handed over) to stand trial in mainland Chinese courts. (Hong Kong also has a separate legal system from the rest of China.) More than a million people participated in the protests. The protesters believed the extradition bill endangered their rights. Hong Kong police clashed with the protesters, who also called for democratic reforms, and many people were arrested or injured. Protesters then added investigations into police brutality to their demands.

On June 15, the Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam (Hong Kong’s governor) suspended the proposed extradition bill, but massive protests continued the next day as more than 2 million people took to the streets. (Hong Kong’s entire population is 7.4 million.) The unrest continued into July as protesters stormed the Hong Kong parliament, ransacking offices and clashing with police. In reaction, pro-Communist government gangs attacked some pro-democracy protesters. Many people were hurt in the confrontations, and hundreds of people were arrested.

The Hong Kong metropolitan area lies on both sides of Victoria Harbour. It includes the northern coast of Hong Kong Island, foreground, and the southern tip of the Kowloon Peninsula, background. Credit: © Leung Chopan, Shutterstock

Amid rising tensions in August, protesters began crowding into police stations as well as into busy Hong Kong International Airport, which was forced to close for several days. Fears of Chinese military intervention—with flashes back to the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989—rose as the army paraded in Shenzhen, just across the border from Hong Kong. Those fears went unrealized, however, and although standoffs between protesters and police continued, violent episodes were relatively rare considering the massive numbers of people involved.

In early September, Chief Executive Lam formally withdrew the extradition bill that ignited the protests. But unrest lingers as the people of Hong Kong continue to push for greater democratic freedoms, universal suffrage (the right to vote), and solutions to housing and land shortages in the densely populated metropolis.

The United Kingdom controlled Hong Kong from 1842 until 1997, when it returned to Chinese control. The “one country, two systems” relationship was created to safeguard the democratic freedoms enjoyed by Hong Kong citizens under British rule. The Chinese government has eroded some of these freedoms, however, and pro-democracy protests have occurred—with much less intensity—in Hong Kong for the last several years.