Mars in Paradise

September 7, 2016

On August 28, six brave explorers breathed the fresh air of Earth for the first time in a year. Since last August, they had been living in an isolated dome, only able to step outside wearing full space suits. They had limited contact with the outside world and had to make do with whatever supplies they had with them. In truth, however, the explorers never left Earth. These six people were simulating what life would be like on a Mars mission—and they were doing it from the “tropical paradise” of Hawaii. The team included a French astrobiologist, a German physicist, and four Americans: an architect, a journalist, a pilot, and a soil scientist.

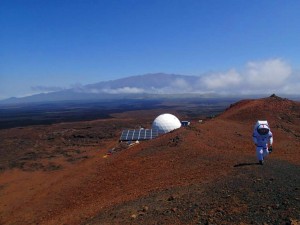

A HI-SEAS team member takes a stroll along the Martian-like slopes of Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii. Credit: © Sian Proctor, University of Hawaii

Mars is the fourth planet from the sun and the next planet beyond Earth in our solar system. Of all the planets in our solar system, Mars has the surface environment that most closely resembles that of Earth. Mars has weather and seasons and familiar landforms. Salty water may flow just below the Martian surface. Because of the Red Planet’s relatively familiar appearance, many see it as the next logical place for human exploration.

The interior of the HI-SEAS dome provides all the comforts of home, or, at least, a home on Mars. Credit: © Zak Wilson, HI-SEAS/University of Hawaii

The six people were part of the fourth Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation (HI-SEAS), conducted by the United States National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). They lived isolated in a dome on Mauna Loa, a huge shield volcano. The craggy red terrain of the volcano resembles the Martian surface. During a HI-SEAS mission, crew members conduct experiments, deal with unforeseen events, and live with limited resources and contact from the outside world. Whenever they left their habitation module to explore the volcano, they would don full space suits. All communication with the rest of the world was delayed by 20 minutes to simulate the time it takes for radio signals to travel between Earth and Mars. The explorers ate bland diets of food that could survive long-duration storage. They also had to maintain their habitat and repair any systems that failed.

On Aug. 28, 2016, happy HI-SEAS explorers “return to Earth” after 365 days of a simulated Mars mission in Hawaii. Credit: © University of Hawaii

While it may sound like high-concept make-believe, experiments like this one will help NASA better prepare future astronauts for long-term space missions, such as a journey to Mars. During such missions, astronauts will be crammed together in small spaces for months or years on end. Simply reaching Mars from Earth will take six months. Maintaining the mental health of the crew will be just as important as keeping any mechanical system in working order. Astronauts will have to cope with boredom and homesickness and avoid interpersonal conflict to accomplish tasks millions of miles from any outside help. The data gathered from HI-SEAS expeditions will help them know what to expect.

This was the longest HI-SEAS mission to date, but it is not the longest Martian simulation. That honor belongs to Russia’s Mars-500 project in 2010-2011, in which another six-person crew endured 520 days of isolation.