A Dinosaur in Its Own Image

Wednesday, September 28th, 2016September 28, 2016

When you see models or illustrations of dinosaurs, have you ever wondered how accurate they are? Bones, skin impressions, and tracks can tell scientists and artists a great deal about the shape, size, and movements of these animals, but how do people know what color patterns the beasts adopted? Most of the time, artists make educated guesses based on what is known about each dinosaur and its habitat. But researchers led by Jakob Vinther of the University of Bristol in the United Kingdom recently collaborated with artist Bob Nicholls to create what may be the most accurate representation of a dinosaur to date. What’s more, the finished model provided clues about the animal’s habitat (rather than the other way around).

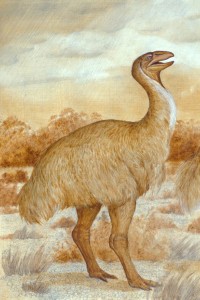

The recently created Psittacosaurus model shows the dinosaur with countershading camouflage (darker on top, lighter on bottom). Many modern-day animals exhibit countershading. Credit: © Jakob Vinther, Robert Nicholls, Stephan Lautenschlager, Michael Pittman, Thomas G. Kaye, Emily Rayfield, Gerald Mayr, Innes C. Cuthill/Univerity of Bristol

Psittacosaurus was a small plant-eating dinosaur that lived 130 million to 100 million years ago in what is now Asia. Its name, which means parrot lizard, comes from its large, sharp, parrotlike beak. The dinosaur measured up to about 2 feet (60 centimeters) tall at the hips and 6 1/2 feet (2 meters) long.

Vinther’s team examined an exquisitely preserved Psittacosaurus from China that included much of its skin. They found that darker areas of skin were full of melanosomes, tiny structures that produce pigments, but the lighter areas were not. This discovery showed that the color pattern seen in the fossil was real, and not the result of discoloration during fossilization.

With that knowledge, the researchers turned to Bob Nicholls, a Bristol-based paleoartist (an artist who specializes in depicting prehistoric life). He carefully examined the specimen, taking into account every minute pattern on the animal’s skin. He then created two sculptures of the animal, painting one a uniform shade of gray, and decorating the other with the intricate patterns seen in the fossil.

From the sculpture, it became clear that Psittacosaurus exhibited countershading. Countershading is a type of camouflage in which the parts of an animal exposed to sunlight are darker colored and the animal’s underside is lighter colored. In sunlight, the exposed, darker-colored sections appear brighter and the lighter-colored sections are shaded by the rest of the body. This effect flattens the appearance of the animal and makes it more difficult to see. Many kinds of animals, from sharks to antelope, exhibit countershading. In the case of Psittacosaurus, this small herbivore (plant eater) was countershaded to try to escape the sight of large meat-eating dinosaurs—relatives of the infamous Tyrannosaurus rex—that lived in the area at the time.

Vinther and his team then took the two sculptures to ecosystems with different lighting characteristics and observed how well camouflaged the countershaded model was in relation to the gray one. They found that the countershaded sculpture was best camouflaged in areas with moderate tree cover, suggesting that this species of Psittacosaurus lived in woodland environments. This evidence also jibes with other fossils that have been found along with the Psittacosaurus, such as petrified tree trunks and remains of shade-loving plants. This is the first time that a dinosaur’s color pattern was used to infer the type of environment in which it lived.

This study showed that determining the colors and color patterns of dinosaurs isn’t just a goal in and of itself, but it can also help define a dinosaur’s ancient environment. It’s not just good for art; it’s good for science!